The cover for Metastatic Memories is done! My very good friend, John Langan, designed it based on a drawing I did in Middle School. John and I go way back -- all the way, like, a few years ago to college. Okay, probably close to seven years. Which can qualify as "way back" if you only have a span of 28 years to pull from.

I'm ecstatic about the way the cover turned out. It holds a great deal of symbolism and emotion. Transfixing, is a good word to describe the finished product. It's the perfect image to reflect the feel of the words inside. John and his fiance' own a design firm catering to a variety of needs. Check out their website, or like their Facebook page.

Without further ado, here's the cover of Metastatic Memories:

And here's the drawing it's based on:

I'm happy to report that editing is going well. You can expect the release of Metastatic Memories at the end of March. Read more about the book here.

Showing posts with label Immunotherapy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Immunotherapy. Show all posts

Friday, March 7, 2014

Friday, January 10, 2014

Upcoming Interview With CRI

I had an interview recently with the Cancer Research Institute, the leading advocacy group for immunotherapy research, about my experience with the treatment and my life since. I won't spoil anything, but in my completely objective and unbiased opinion, I think it may be the greatest interview since Frost/Nixon.

I kid. But it's still a worthwhile read. In it, I talk about my approach to life after cancer, my relationships with those important to me, and what I'm trying to do with my life now that it's been given back to me. It's not a bad little tale, mine. And it reminds me every day to try my best to realize all of the lofty goals that popped into my head immediately after I was diagnosed. Most of them were common sense, but things that still seemed so impossible to take action toward. That is, until the threat of impending death forces your hand. When you realize you have a very concrete deadline to accomplish whatever it is you believe you're here for, you start working a little harder to get it done. In my case, spending time with those closest to me, helping out as much as I can to make the world a little better than it was when I got here, and living life on my own terms are what's important. There are many specifics involved in each of those, but we'll save that for another post.

The interview will run in print to subscribers. And anyone can see the extended interview and extra pictures from the shoot on CRI's website. I'll let everyone know when it's up. Happy reading.

|

| When a cancer survivor does it, it's not a crime! |

I kid. But it's still a worthwhile read. In it, I talk about my approach to life after cancer, my relationships with those important to me, and what I'm trying to do with my life now that it's been given back to me. It's not a bad little tale, mine. And it reminds me every day to try my best to realize all of the lofty goals that popped into my head immediately after I was diagnosed. Most of them were common sense, but things that still seemed so impossible to take action toward. That is, until the threat of impending death forces your hand. When you realize you have a very concrete deadline to accomplish whatever it is you believe you're here for, you start working a little harder to get it done. In my case, spending time with those closest to me, helping out as much as I can to make the world a little better than it was when I got here, and living life on my own terms are what's important. There are many specifics involved in each of those, but we'll save that for another post.

The interview will run in print to subscribers. And anyone can see the extended interview and extra pictures from the shoot on CRI's website. I'll let everyone know when it's up. Happy reading.

Tuesday, December 24, 2013

Flu Vaccine Myths: A Young Adult Cancer Survivor Dispels The Misconceptions

It's that time of year again, when people crawl out of the woodwork shouting the failures of hundreds of years of technological advancements to the heavens. The bandwagon of mistrust in big government, big pharma, big bad doctors, and misplaced faith in big unsubstantiated opinions is about to grow three-fold like the Grinch's heart on Christmas morning. This is, after all, flu season.

The Facebook posts are running rampant: "Flu vaccine kills one boy in Texas;" "Six grandmothers in Detroit;" "Three hundred groundhogs in Montana;" "One hundred and one Arabian Nights;" and, "Twelve dancers dancing during a popular holiday sing-a-long before horrified onlookers."

Sometimes, they're framed in the form of questions designed to incite sensational reactions from the public:

"Is the flu vaccine useful?" "Does it work?" "Should we stop getting the flu shot?" "Should we stop waiting for traffic lights and wearing seat belts?" "Is eating raccoon poop really going to kill us anymore? I sprinkled some on my oatmeal this morning and I feel just fine." "Are grizzly bears suddenly the best holiday gifts for teens?"

Some of these headlines are disturbing. But make no mistake, they are all completely and unquestionably real, aside from the ones that are not.

I'm going to talk about the most common misconceptions regarding the flu vaccine, and why it's still essential that every living human do their duty to the species and get jabbed in the arm with a needle this holiday season. I will be using my unique perspective as a cancer survivor to talk about some of the immunological aspects of vaccination science. Try to relax, you may feel a little pinch.

1.) The Flu Vaccine Causes The Flu

This is completely impossible. The virus has been modified so that it's unable to proliferate and give you the flu. This is not new science, and it's been used every day for over a century. The shot form of the flu vaccine specifically doesn't even include the actual virus. It's called a subunit vaccine -- a vaccine that only contains certain parts or proteins of a virus in order to solicit an immune response to them. The nasal spray variety includes a strain of flu that's been forcibly evolved by passing it through hundreds of chick eggs in order to create a version of the disease that can't infect humans.

2.) I Always Get The Flu After Getting The Flu Vaccine

You don't (See number 1), but I can explain the reason why you might think that. Your immune system causes most symptoms you experience when you get sick -- headaches, chills, fever, nausea, aches and pains. Your body does all of that stuff to itself. A vaccine is designed to mimic a real infection, thus soliciting a real immune response. In recent years, vaccines have gotten better at diminishing side effects. Some say there shouldn't be any at all with the new rounds of flu vaccines.

Here's an anecdote. When I was going through immunotherapy, I was injecting obscene amounts of a protein called Interferon. Interferon is one of the proteins your body produces to make you feel so crappy when you get sick, and I definitely felt like I was sick all the time. That was coincidentally the year my boosters were up, and I ended up getting the flu shot, pneumonia vaccine, and the tetanus shot all at the same time. I ended up in the hospital, and after they pumped a bag of fluids into my arm, I felt a little better. Though I'm informed enough to know that the reason for this was my body's immune response to the vaccines, on top of my already overwhelmed immune system. My case was a fluke, but, subsequently, if you're currently undergoing treatment for cancer, you should consult your PCP and your oncologist to find out about side effects.

The American Cancer Society recommends that all patients get the flu shot. Read a summary of their recommendations here.

3.) Vaccines Don't Work

This is false. Edward Jenner was born in 1749. He developed an hypothesis that contracting cowpox would prevent a person from coming down with deadly smallpox. This is actually where the word vaccine originates -- from the Latin vaccinus, or, "pertaining to cows." Smallpox was eradicated from the planet in 1980. Notice how long it took to eradicate the disease from the time a solution was discovered. The reasons for this are, 1.) this was the first major step and represents the early days of vaccination science, and 2.) viruses are effing complicated. They're persistent, fast-evolving, complex organisms. Scientists have to scramble to figure out the best ways to deal with them. The flu is one of the most complicated viruses around. Seriously, look up the science, the flu is a tricky mistress. Start your research here with an article from BBC Science about the complexity of viruses and why they're so hard to beat. In the case of the flu, it's still difficult to predict which strains will run rampant each flu season with 100% accuracy, but getting the shot will offer some measure of protection regardless. And, to be fair to smallpox research, a campaign to globally eliminate the disease wasn't undertaken until 1959. If you're interested, you can read more about the history of the disease and its eradication here.

And here's a nifty bulletin from the WHO providing stats and figures for the successful use of vaccines, including the fact that in the U.S., incidence of infection from the nine diseases recommended for vaccination has decreased by 99%.

4.) Vaccines Contain Terrible, Awful, No Good, Very Bad Ingredients

The most commonly-cited ingredients of the flu vaccine are mercury and formaldehyde. Okay, let's talk a little about chemistry for a moment. Mercury is an element. It can be found in different chemicals and substances, just like any other element. The ingredient in question is called thimerosal, which breaks down into ethylmercury. Ethylmercury is a substance that metabolizes quickly and exits the body without causing a toxic build-up of mercury. Again, this is the type found in vaccines in the form of the preservative, thimerosal. The dangerous sort, methylmercury, bio-accumulates through the food chain and can build up in the body through dietary intake, and create all sorts of risk factors to an individual's health. This is why women aren't supposed to eat certain fish while pregnant -- the kind like shark and swordfish that are at the top of the food chain, because they'll have high concentrations of mercury coursing through them due to all the lower inhabitants of the food chain also consuming methylmercury. Environmental contamination of mercury is also a factor in choosing your fish. If you don't care much for facts and still like the idea of having mercury in your shot regardless, you can ask to have one without thimerosal in it.

Formaldehyde is an organic chemical that occurs naturally in the body. But, like most everything else, too much of it can be a bad thing. It's produced internally, and we ingest it daily through our diet and other means, like breathing. Formaldehyde is everywhere. Though, it also metabolizes quickly, and doesn't easily accumulate. The fact is, you get more formaldehyde by eating a pear than you do from the flu vaccine. Here's a convenient guide. Highlights to keep in mind: the most formaldehyde you'll probably get from vaccines will come when you're a baby, at the six-month checkup, and the amount will be 160 times less than the amount naturally produced by your body every single day.

There are other ingredients cited, and they all have equally reasonable and mundane chemical explanations. Why not do some reading?

5.) My Decision To Abstain From Getting Vaccinated Doesn't Hurt You

This is a reasonable thing to think. Because, what you do is your business, right? Well, not in the case of public health. It turns out, there's a thing called Community Immunity, or (an even sillier though less poetic name) Herd Immunity. Herd Immunity is a state or condition that's met when a sufficient amount of the population is immunized against a given disease, cited around 75-95%, though it varies for specific diseases. Herd Immunity provides a safety net for society, and allows us to successfully contain a virus. If you don't get vaccinated, you're running a cost-benefit analysis and playing a fun casino home-game. Only when you lose, the risks may be a little higher than you bargained for, and include the extermination of the human race. By not getting inoculated, you're providing a medium for the flu to evolve and become even harder to beat. Herd Immunity is a complex science, and you can read more about it here.

There you have it. Those are the top flu myths around, and, conveniently, my own personal favorites. There are many other false claims and misconceptions about the flu vaccine, such as, they cause autism, asthma, allergies, Alzheimer's, narcolepsy, blood disorders, the starving of puppies, your parents' divorce, and that they're descended directly from an intimate meeting between Satan and all those Hugo Weaving characters from Cloud Atlas. I won't go into these, because there is absolutely no clinical research to show that there is merit to any of them, and a whole lot of research that says they're bunk.

Parting tip: Always be wary of claims suggesting the rise in a certain disease or condition is dependent on any man-made means -- the rise of rates is proportional to the rise in population (i.e. there are more people, so there will be more cases of X). Make sure to do your own research and be your own advocate, but, at the same time, pay attention to the actual research. Facts are important.

There are other flu vaccine guides out there on the interwebs, including this one from Gizmodo, which is extremely thorough and comprehensive.

The Facebook posts are running rampant: "Flu vaccine kills one boy in Texas;" "Six grandmothers in Detroit;" "Three hundred groundhogs in Montana;" "One hundred and one Arabian Nights;" and, "Twelve dancers dancing during a popular holiday sing-a-long before horrified onlookers."

Sometimes, they're framed in the form of questions designed to incite sensational reactions from the public:

"Is the flu vaccine useful?" "Does it work?" "Should we stop getting the flu shot?" "Should we stop waiting for traffic lights and wearing seat belts?" "Is eating raccoon poop really going to kill us anymore? I sprinkled some on my oatmeal this morning and I feel just fine." "Are grizzly bears suddenly the best holiday gifts for teens?"

Some of these headlines are disturbing. But make no mistake, they are all completely and unquestionably real, aside from the ones that are not.

I'm going to talk about the most common misconceptions regarding the flu vaccine, and why it's still essential that every living human do their duty to the species and get jabbed in the arm with a needle this holiday season. I will be using my unique perspective as a cancer survivor to talk about some of the immunological aspects of vaccination science. Try to relax, you may feel a little pinch.

1.) The Flu Vaccine Causes The Flu

This is completely impossible. The virus has been modified so that it's unable to proliferate and give you the flu. This is not new science, and it's been used every day for over a century. The shot form of the flu vaccine specifically doesn't even include the actual virus. It's called a subunit vaccine -- a vaccine that only contains certain parts or proteins of a virus in order to solicit an immune response to them. The nasal spray variety includes a strain of flu that's been forcibly evolved by passing it through hundreds of chick eggs in order to create a version of the disease that can't infect humans.

2.) I Always Get The Flu After Getting The Flu Vaccine

You don't (See number 1), but I can explain the reason why you might think that. Your immune system causes most symptoms you experience when you get sick -- headaches, chills, fever, nausea, aches and pains. Your body does all of that stuff to itself. A vaccine is designed to mimic a real infection, thus soliciting a real immune response. In recent years, vaccines have gotten better at diminishing side effects. Some say there shouldn't be any at all with the new rounds of flu vaccines.

Here's an anecdote. When I was going through immunotherapy, I was injecting obscene amounts of a protein called Interferon. Interferon is one of the proteins your body produces to make you feel so crappy when you get sick, and I definitely felt like I was sick all the time. That was coincidentally the year my boosters were up, and I ended up getting the flu shot, pneumonia vaccine, and the tetanus shot all at the same time. I ended up in the hospital, and after they pumped a bag of fluids into my arm, I felt a little better. Though I'm informed enough to know that the reason for this was my body's immune response to the vaccines, on top of my already overwhelmed immune system. My case was a fluke, but, subsequently, if you're currently undergoing treatment for cancer, you should consult your PCP and your oncologist to find out about side effects.

The American Cancer Society recommends that all patients get the flu shot. Read a summary of their recommendations here.

3.) Vaccines Don't Work

This is false. Edward Jenner was born in 1749. He developed an hypothesis that contracting cowpox would prevent a person from coming down with deadly smallpox. This is actually where the word vaccine originates -- from the Latin vaccinus, or, "pertaining to cows." Smallpox was eradicated from the planet in 1980. Notice how long it took to eradicate the disease from the time a solution was discovered. The reasons for this are, 1.) this was the first major step and represents the early days of vaccination science, and 2.) viruses are effing complicated. They're persistent, fast-evolving, complex organisms. Scientists have to scramble to figure out the best ways to deal with them. The flu is one of the most complicated viruses around. Seriously, look up the science, the flu is a tricky mistress. Start your research here with an article from BBC Science about the complexity of viruses and why they're so hard to beat. In the case of the flu, it's still difficult to predict which strains will run rampant each flu season with 100% accuracy, but getting the shot will offer some measure of protection regardless. And, to be fair to smallpox research, a campaign to globally eliminate the disease wasn't undertaken until 1959. If you're interested, you can read more about the history of the disease and its eradication here.

And here's a nifty bulletin from the WHO providing stats and figures for the successful use of vaccines, including the fact that in the U.S., incidence of infection from the nine diseases recommended for vaccination has decreased by 99%.

4.) Vaccines Contain Terrible, Awful, No Good, Very Bad Ingredients

The most commonly-cited ingredients of the flu vaccine are mercury and formaldehyde. Okay, let's talk a little about chemistry for a moment. Mercury is an element. It can be found in different chemicals and substances, just like any other element. The ingredient in question is called thimerosal, which breaks down into ethylmercury. Ethylmercury is a substance that metabolizes quickly and exits the body without causing a toxic build-up of mercury. Again, this is the type found in vaccines in the form of the preservative, thimerosal. The dangerous sort, methylmercury, bio-accumulates through the food chain and can build up in the body through dietary intake, and create all sorts of risk factors to an individual's health. This is why women aren't supposed to eat certain fish while pregnant -- the kind like shark and swordfish that are at the top of the food chain, because they'll have high concentrations of mercury coursing through them due to all the lower inhabitants of the food chain also consuming methylmercury. Environmental contamination of mercury is also a factor in choosing your fish. If you don't care much for facts and still like the idea of having mercury in your shot regardless, you can ask to have one without thimerosal in it.

Formaldehyde is an organic chemical that occurs naturally in the body. But, like most everything else, too much of it can be a bad thing. It's produced internally, and we ingest it daily through our diet and other means, like breathing. Formaldehyde is everywhere. Though, it also metabolizes quickly, and doesn't easily accumulate. The fact is, you get more formaldehyde by eating a pear than you do from the flu vaccine. Here's a convenient guide. Highlights to keep in mind: the most formaldehyde you'll probably get from vaccines will come when you're a baby, at the six-month checkup, and the amount will be 160 times less than the amount naturally produced by your body every single day.

There are other ingredients cited, and they all have equally reasonable and mundane chemical explanations. Why not do some reading?

5.) My Decision To Abstain From Getting Vaccinated Doesn't Hurt You

This is a reasonable thing to think. Because, what you do is your business, right? Well, not in the case of public health. It turns out, there's a thing called Community Immunity, or (an even sillier though less poetic name) Herd Immunity. Herd Immunity is a state or condition that's met when a sufficient amount of the population is immunized against a given disease, cited around 75-95%, though it varies for specific diseases. Herd Immunity provides a safety net for society, and allows us to successfully contain a virus. If you don't get vaccinated, you're running a cost-benefit analysis and playing a fun casino home-game. Only when you lose, the risks may be a little higher than you bargained for, and include the extermination of the human race. By not getting inoculated, you're providing a medium for the flu to evolve and become even harder to beat. Herd Immunity is a complex science, and you can read more about it here.

There you have it. Those are the top flu myths around, and, conveniently, my own personal favorites. There are many other false claims and misconceptions about the flu vaccine, such as, they cause autism, asthma, allergies, Alzheimer's, narcolepsy, blood disorders, the starving of puppies, your parents' divorce, and that they're descended directly from an intimate meeting between Satan and all those Hugo Weaving characters from Cloud Atlas. I won't go into these, because there is absolutely no clinical research to show that there is merit to any of them, and a whole lot of research that says they're bunk.

Parting tip: Always be wary of claims suggesting the rise in a certain disease or condition is dependent on any man-made means -- the rise of rates is proportional to the rise in population (i.e. there are more people, so there will be more cases of X). Make sure to do your own research and be your own advocate, but, at the same time, pay attention to the actual research. Facts are important.

There are other flu vaccine guides out there on the interwebs, including this one from Gizmodo, which is extremely thorough and comprehensive.

Friday, December 20, 2013

My Cancer Brings All the Crazies to the Yard

In today's day and age, it's important for the patient to be his or her own advocate. It's an unfortunate reality, but as soon as something happens to you, you've unwittingly opened yourself to an entirely new world that you may not be prepared to successfully navigate. And, while doing your best to focus on the issue at hand, it's easy to be taken in by snake oil and pseudoscience. There's nothing worse than a cancer opportunist -- someone who uses your illness to his or her advantage, pushing ineffective and sometimes dangerous products and treatments. I talk about some of my favorite fake treatments in another post, The Dangers of Alternative Health: 3 Treatments That Can Cause Some Serious Damage.

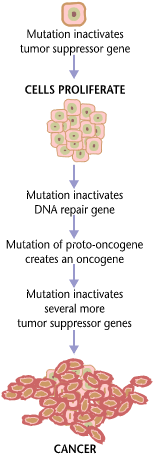

The thing about cancer is that it's a biological process -- several, in fact, occurring simultaneously. Cancer is a series of genetic and epigenetic malfunctions. It isn't caused by any solitary force. And it certainly isn't caused by mysterious "toxins" with no names or identities. It isn't caused by your attitude either, or your karma (by the way, the western definition of karma is not even entirely accurate), or even when your room mate peed in the mini fridge in your dorm room the night he was really drunk.

Having cancer is a desperate situation for many people. And it brings out the best and worst of the human race. There are several reasons to be wary of anyone who tries to sell you something when you need it most. The sad fact is that many people fall prey to these villains, foregoing entry into legitimate treatment programs and significantly decreasing their odds of survival.

The first and most important line of defense is to do your research. In today's culture, fact-checking has become a long-forgotten practice. Claims are made, and whoever yells the loudest is always declared the most honest. That's not how science works, unfortunately. In the real world, experts propose hypotheses and test them until they can be fully evaluated and verified. And, as Neil deGrasse Tyson put it, "The good thing about science is that it's true whether or not you believe in it."

For whatever reason, the age of information has had the opposite effect of informing the public. It could be that with all of this information at hand, it makes it easier for people to believe that they know much more about a particular issue than they really do. It still takes years of schooling to become an expert in a given field, like oncology. The danger arises among those who falsely profess a knowledge of healthcare and push miracle cures on the public that only they have uncovered through collecting pee from public parks, or shooting coffee into your rectum. It's not easy to determine whether or not modern snake oil salesmen peddle their wares with the intention of making money from their faulty products, or if they genuinely think what they're doing will provide some benefit. I tend to believe the former in most cases. The current state of healthcare in America reminds me of my favorite quote by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov: "Anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that 'my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.'"

All of these alternative therapies will bankrupt you, because they're obscenely expensive and your insurance won't pay for them, because they aren't medicine. Mainstream healthcare is also extremely expensive, to be fair, and the U.S. is by far the most expensive nation in which to get sick. But there is a mechanism in place to at least ensure that a patient can find treatment backed by real medical science. If you aren't sure how to find out whether or not a treatment is bogus, just look for the clinical research. Real treatments are published, peer-reviewed, and independently verified over a number of years in order to ensure their safety and effectiveness. Cancer is tricky, because we can't at this point cure it, and that scares many people into thinking that's because traditional treatments don't work, when really it's just the best we can do at this point. With the advent of new immunotherapy research, results and patient outcomes are looking even more promising these days, and we can expect a new wave of even more effective treatments very soon. Human innovation is a process. Yes, people are greedy, and things still cost money. But the most villainous and greedy among us are the opportunists who take advantage of the desperation of others.

The thing about cancer is that it's a biological process -- several, in fact, occurring simultaneously. Cancer is a series of genetic and epigenetic malfunctions. It isn't caused by any solitary force. And it certainly isn't caused by mysterious "toxins" with no names or identities. It isn't caused by your attitude either, or your karma (by the way, the western definition of karma is not even entirely accurate), or even when your room mate peed in the mini fridge in your dorm room the night he was really drunk.

|

| The process looks like this. |

The first and most important line of defense is to do your research. In today's culture, fact-checking has become a long-forgotten practice. Claims are made, and whoever yells the loudest is always declared the most honest. That's not how science works, unfortunately. In the real world, experts propose hypotheses and test them until they can be fully evaluated and verified. And, as Neil deGrasse Tyson put it, "The good thing about science is that it's true whether or not you believe in it."

For whatever reason, the age of information has had the opposite effect of informing the public. It could be that with all of this information at hand, it makes it easier for people to believe that they know much more about a particular issue than they really do. It still takes years of schooling to become an expert in a given field, like oncology. The danger arises among those who falsely profess a knowledge of healthcare and push miracle cures on the public that only they have uncovered through collecting pee from public parks, or shooting coffee into your rectum. It's not easy to determine whether or not modern snake oil salesmen peddle their wares with the intention of making money from their faulty products, or if they genuinely think what they're doing will provide some benefit. I tend to believe the former in most cases. The current state of healthcare in America reminds me of my favorite quote by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov: "Anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that 'my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.'"

All of these alternative therapies will bankrupt you, because they're obscenely expensive and your insurance won't pay for them, because they aren't medicine. Mainstream healthcare is also extremely expensive, to be fair, and the U.S. is by far the most expensive nation in which to get sick. But there is a mechanism in place to at least ensure that a patient can find treatment backed by real medical science. If you aren't sure how to find out whether or not a treatment is bogus, just look for the clinical research. Real treatments are published, peer-reviewed, and independently verified over a number of years in order to ensure their safety and effectiveness. Cancer is tricky, because we can't at this point cure it, and that scares many people into thinking that's because traditional treatments don't work, when really it's just the best we can do at this point. With the advent of new immunotherapy research, results and patient outcomes are looking even more promising these days, and we can expect a new wave of even more effective treatments very soon. Human innovation is a process. Yes, people are greedy, and things still cost money. But the most villainous and greedy among us are the opportunists who take advantage of the desperation of others.

Labels:

Alternative Medicine,

Cancer,

Healthcare,

Immunotherapy,

Isaac Asimov,

Neil deGrasse Tyson,

Science

Fifty Shades of Kevin: A Dramatic Reading

My friends and I have been renting a cabin at Cook Forest in Clarion for the past few summers. We stay for a long weekend, and get into as much trouble as we possibly can. The first year we went, I was undergoing immunotherapy treatment for stage 3 melanoma, and I was shocked at how much fun I had despite the side effects. The fatigue and other symptoms were mostly forgotten, and for the most part I could keep up with the festivities. This year, we were at it again. It just so happened that this time around one of our friends brought along a copy of 50 Shades. Since none of us have age-appropriate maturity levels, we couldn't help but to pass the book around for dramatic readings. Mine starts off in Standard American i.e. Shakespeare, and quickly deteriorates into a bad Dustin Hoffman from Hook. Watch my personal interpretation of a passage from the book below.

Wednesday, December 11, 2013

Holiday Cheer, With A Little Death Mixed In

I realize I would have thrown up this morning, had I let myself. This morning, all of last night, and probably all of yesterday had I not been occupying my time playing video games. My mother came down at eleven to say goodnight. “Are you going to bed?” she asked. I told her I would. “Are you worried?” she asked. I blew up in her face, because I’d been marathon-ing Skyrim precisely so I wouldn’t have to think about how worried I was. It was some time before we were able to settle the issue and she went to bed.

This morning was six days after the stuffing, the cranberry sauce, the turkey coma, and the mashed potatoes with the butter poured in the middle to dip in. Six days after I’d made all the pies: an apple, a pumpkin, an apple dumpling, and a mighty scrumptious pumpkin cheesecake. I’m still home for the holiday. My girlfriend left on Sunday, and I wasn’t able to go with her. We found a mass Wednesday night, just before Thanksgiving. I had been diagnosed with cancer in 2011 at the age of 25, so I kept my potential recurrence to myself through the holiday, since I’d seen the effects of this kind of news firsthand, and I didn’t want to ruin the festivities for everyone.

This morning was also four days after the champagne toast my mother arranged to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the completion of my cancer treatment. “What’s the best kind of champagne?” she’d asked me just days before. “Can you get some cheap?” I’d learned from a college roommate that Korbel was the best cheap champagne and I told her so. I immediately knew something was up, because she only asks me questions like that when she’s getting me something. And I couldn’t for the life of me figure out why she would be getting me champagne. Cancer was that far from my mind. Then I found the mass, and I had felt like a fraud, clinking glasses, smiling around the table, knowing full-well that I might once again be actively dying.

No matter the outcome of the poking and prodding that was to come, I was once again faced with the knowledge that I had had cancer, and that I’d had three surgeries and an awful, year-long treatment to prevent it from coming back, all in my mid-twenties. And that being so young, I had significant reason to think it might rear its ugly head sometime down the long road ahead.

There was a New York Times article about this over the summer. The quoted findings, from Dr. Alex J. Mitchell at the University of Leicester, stated that 18% of young adults remain severely anxious about their experience with cancer two to ten years after being diagnosed. In couples, that number rose to 28%, with 40% of spouses reporting above-average levels. The anxiety is real. I feel the complete set of fears rise up in my neck, the pain of every hair on my body standing sharply at attention, whenever I think I might have found something suspicious poking out. And that will never change. I feel guilty every day because I’m in a happy, healthy relationship with someone I truly care about, and what all this must mean for her.

Studies also suggest the same is true of depression, though I’ve personally avoided the brunt of that. Aside from a stint with chemical depression induced by my immunotherapy treatment, I’ve been my father’s son -- an unfailing optimist. When I was first diagnosed, and during the ensuing year of treatment, which some refer to with such cavalier terms as “battle,” “struggle,” or some other equally obnoxious buzzword, I went to therapy regularly to work through a healthy episode of PTSD. According to a study done by Dr. Mary Rourke at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, I’m not alone there either. By evaluating one hundred eighty-two survivors of pediatric cancers, she found that 16% had PTSD. Dr. Rourke concluded that young adult cancer survivors experience more psychological problems than the general population.

It’s no wonder then, sitting over my healthy serving of dark meat, watching my family laugh and drink, watching my girlfriend for any obvious signs of hating my family, that I felt a sense of dread underneath it all. What if I don’t have many more occasions like this? No more holidays, no more fun times with the family, no more hoping my girlfriend will get along with the craziest, most inappropriate members of my clan. Looking around the table at the smiling faces, I asked myself, what if I don’t have any more holidays at all?

This morning I had an ultrasound at the local hospital in town. My family doctor doesn’t have the little stick thingy or the gel at his office, so they made me wait while the hospital took forever to schedule an appointment for today. To my (pseudo) relief, the tech didn’t see anything unusual. My Physician Assistant best friend reminds me that techs are not doctors, and the official results are still pending. I am not fully relieved, nor will I ever be.

I am now 28 years old, and this is what I’ll be doing for the rest of my life. I love my family, and my friends, and I hope to have a long, prosperous life in a career that satisfies me, with a partner by my side who complements me and fills me with joy. There is a dark cloud that lingers above me, threatening to take it all away at a moment’s notice. I willingly pay it no mind when it’s unreasonable to do so, but that only means that when I have a legitimate scare, it comes back in full force. It took a long time to come to terms with this pattern, but I realize that it will always be a force in my life. Only at times like Thanksgiving, when I can sit around a table with the people who are most important, laugh, play games, and drink cheap champagne, that I realize how lucky I am to have had any of it at all.

This morning was six days after the stuffing, the cranberry sauce, the turkey coma, and the mashed potatoes with the butter poured in the middle to dip in. Six days after I’d made all the pies: an apple, a pumpkin, an apple dumpling, and a mighty scrumptious pumpkin cheesecake. I’m still home for the holiday. My girlfriend left on Sunday, and I wasn’t able to go with her. We found a mass Wednesday night, just before Thanksgiving. I had been diagnosed with cancer in 2011 at the age of 25, so I kept my potential recurrence to myself through the holiday, since I’d seen the effects of this kind of news firsthand, and I didn’t want to ruin the festivities for everyone.

This morning was also four days after the champagne toast my mother arranged to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the completion of my cancer treatment. “What’s the best kind of champagne?” she’d asked me just days before. “Can you get some cheap?” I’d learned from a college roommate that Korbel was the best cheap champagne and I told her so. I immediately knew something was up, because she only asks me questions like that when she’s getting me something. And I couldn’t for the life of me figure out why she would be getting me champagne. Cancer was that far from my mind. Then I found the mass, and I had felt like a fraud, clinking glasses, smiling around the table, knowing full-well that I might once again be actively dying.

No matter the outcome of the poking and prodding that was to come, I was once again faced with the knowledge that I had had cancer, and that I’d had three surgeries and an awful, year-long treatment to prevent it from coming back, all in my mid-twenties. And that being so young, I had significant reason to think it might rear its ugly head sometime down the long road ahead.

There was a New York Times article about this over the summer. The quoted findings, from Dr. Alex J. Mitchell at the University of Leicester, stated that 18% of young adults remain severely anxious about their experience with cancer two to ten years after being diagnosed. In couples, that number rose to 28%, with 40% of spouses reporting above-average levels. The anxiety is real. I feel the complete set of fears rise up in my neck, the pain of every hair on my body standing sharply at attention, whenever I think I might have found something suspicious poking out. And that will never change. I feel guilty every day because I’m in a happy, healthy relationship with someone I truly care about, and what all this must mean for her.

Studies also suggest the same is true of depression, though I’ve personally avoided the brunt of that. Aside from a stint with chemical depression induced by my immunotherapy treatment, I’ve been my father’s son -- an unfailing optimist. When I was first diagnosed, and during the ensuing year of treatment, which some refer to with such cavalier terms as “battle,” “struggle,” or some other equally obnoxious buzzword, I went to therapy regularly to work through a healthy episode of PTSD. According to a study done by Dr. Mary Rourke at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, I’m not alone there either. By evaluating one hundred eighty-two survivors of pediatric cancers, she found that 16% had PTSD. Dr. Rourke concluded that young adult cancer survivors experience more psychological problems than the general population.

It’s no wonder then, sitting over my healthy serving of dark meat, watching my family laugh and drink, watching my girlfriend for any obvious signs of hating my family, that I felt a sense of dread underneath it all. What if I don’t have many more occasions like this? No more holidays, no more fun times with the family, no more hoping my girlfriend will get along with the craziest, most inappropriate members of my clan. Looking around the table at the smiling faces, I asked myself, what if I don’t have any more holidays at all?

This morning I had an ultrasound at the local hospital in town. My family doctor doesn’t have the little stick thingy or the gel at his office, so they made me wait while the hospital took forever to schedule an appointment for today. To my (pseudo) relief, the tech didn’t see anything unusual. My Physician Assistant best friend reminds me that techs are not doctors, and the official results are still pending. I am not fully relieved, nor will I ever be.

I am now 28 years old, and this is what I’ll be doing for the rest of my life. I love my family, and my friends, and I hope to have a long, prosperous life in a career that satisfies me, with a partner by my side who complements me and fills me with joy. There is a dark cloud that lingers above me, threatening to take it all away at a moment’s notice. I willingly pay it no mind when it’s unreasonable to do so, but that only means that when I have a legitimate scare, it comes back in full force. It took a long time to come to terms with this pattern, but I realize that it will always be a force in my life. Only at times like Thanksgiving, when I can sit around a table with the people who are most important, laugh, play games, and drink cheap champagne, that I realize how lucky I am to have had any of it at all.

Labels:

Anxiety,

Cancer,

Depression,

Holidays,

Immunotherapy,

Young Adult Cancer Survivors

Friday, October 11, 2013

Graduation Day: Dying From Cancer To Clean Scans In One Easy Step

I had my checkup at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center recently. In the days leading up to the appointment, I was, as always, irrationally paranoid about every bump and bruise and utterly convinced that I had only days left to live. "What the hell is that??" I'd say in the shower, only to find that the offending lump was in fact some completely normal anatomical part that was supposed to be where it was and had been for the prior 28 years of my life. One day I found something really large that turned out to be my bicep. Is it supposed to feel like that?? Jesus.

I'm pretty convinced that I also manufactured a crisis by feeling up the nodes in my thigh so much that I bruised the area around my junk, causing me to worry about the "strange sensation" so much that I began to formulate my last goodbyes and figure out who I should give my surplus of Magic cards to (they aren't even legal to play anymore, but what did you expect from a young adult cancer survivor -- a current deck of Magic cards? What, am I made of money?). At the appointment, the PA noticed similar bruising in the nodes between my armpit and chest, which had previously been described to me as "bumpy." It was at this point I wondered if I could actually give myself cancer from checking so hard for signs of cancer. Or at the very least, a severe case of internal bleeding. Then I thought of the scenes from every medical drama in history where the doctor comes out and says very sadly, "I'm sorry, we can't stop the bleeding." And I think to myself, Wait, what? Don't you have like science and bags of other people's blood and stuff like that? I mean, wrap it in a t-shirt for God's sake. And I think of how much I would really disapprove of being the subject of one of those scenes because I pressed too hard while checking my nodes.

I did my X-Ray, blood work, and obligatory waiting room meditation before they called me back and stripped me down. I met a new PA student who checked me over and wanted to talk about what I was doing in life, and all the bizarrely existential things people say to one another with eerie lightness during an initial meeting, and all I could think about was how bumpy my nodes were. I stumbled through the conversation until the regular PA came in, who I'm very comfortable with and who has made this whole close to death thing a little less crappy. As it turns out, all my worrying was for nothing (isn't it always? Worrying is, by its very nature, useless). The X-Ray was clear, which meant my core was not filled with death, and the blood work confirmed that, yes, my blood was mostly made of blood, and not terrifying cancer Legos waiting to combine into a macabre pirate ship and sail right into my brain (though the castle Legos were my favorite [and I always made my mother buy them for Christmas and then put them together for me. It was obvious at an early age that I wasn't going to be an engineer.).].

We talked for a while, because, even though we meet routinely at an appointed time to make certain I'm not actively dying, I like to think that she and I are friends. Then, suddenly, she informed me that I had graduated to six months. I was surprised, because I didn't think I'd be at six months for several years. "Nope," she said. "One year after diagnosis you go to four, and two years after you graduate to six." I went into this appointment convinced that I'd have to replay the scenario after my diagnosis where I went around telling everyone I was going to die, and that I loved them. And I came out of it not only with a clean bill of health, but with the added bonus of being considered healthy enough to last an extra two months on my own at a time.

As a young adult cancer survivor, I will never stop worrying about dying before I've lived long enough to leave my mark, to positively affect the world, and do whatever other things my mother would no doubt disapprove of. Every time I make the trip to the doctor, all of the emotions surrounding my initial diagnosis come flooding back. But in a strange, dissociated kind of way because the memories have faded, and all I really feel now is that I'm submerged underwater in a claustrophobic sea of negativity. The sensation causes me to find things that aren't there, and to worry myself into a bad place. I blame this partially on the come down from surviving cancer, the getting back to "normal." I have a wealth of experience with life and death and priorities and trivialities, intense emotions spawning from serious existential crisis, and the lessons that facing a terminal illness can teach you. But all of this fades when the tests start to come back clean, and distance begins to seep in between you and what almost prematurely ended you. In the future, I'd like to be more conscious of the divide, and learn how to better reconcile the urgency I used to feel with the humdrum of daily life. It's a lofty goal, though I'm sure it's possible. I'm not the only cancer survivor, stumbling through life trying to make sense of it all. I'm sure I'll get there. After all, I have at least six months to do it.

Photo credits: Top -- A doctor looks at an x-ray, by Ron Mahon

I'm pretty convinced that I also manufactured a crisis by feeling up the nodes in my thigh so much that I bruised the area around my junk, causing me to worry about the "strange sensation" so much that I began to formulate my last goodbyes and figure out who I should give my surplus of Magic cards to (they aren't even legal to play anymore, but what did you expect from a young adult cancer survivor -- a current deck of Magic cards? What, am I made of money?). At the appointment, the PA noticed similar bruising in the nodes between my armpit and chest, which had previously been described to me as "bumpy." It was at this point I wondered if I could actually give myself cancer from checking so hard for signs of cancer. Or at the very least, a severe case of internal bleeding. Then I thought of the scenes from every medical drama in history where the doctor comes out and says very sadly, "I'm sorry, we can't stop the bleeding." And I think to myself, Wait, what? Don't you have like science and bags of other people's blood and stuff like that? I mean, wrap it in a t-shirt for God's sake. And I think of how much I would really disapprove of being the subject of one of those scenes because I pressed too hard while checking my nodes.

|

| "I've taken out half of your bones and hung them on this pole here, and from these scans it looks like all of your blood has come with it. I've done everything I can." |

I did my X-Ray, blood work, and obligatory waiting room meditation before they called me back and stripped me down. I met a new PA student who checked me over and wanted to talk about what I was doing in life, and all the bizarrely existential things people say to one another with eerie lightness during an initial meeting, and all I could think about was how bumpy my nodes were. I stumbled through the conversation until the regular PA came in, who I'm very comfortable with and who has made this whole close to death thing a little less crappy. As it turns out, all my worrying was for nothing (isn't it always? Worrying is, by its very nature, useless). The X-Ray was clear, which meant my core was not filled with death, and the blood work confirmed that, yes, my blood was mostly made of blood, and not terrifying cancer Legos waiting to combine into a macabre pirate ship and sail right into my brain (though the castle Legos were my favorite [and I always made my mother buy them for Christmas and then put them together for me. It was obvious at an early age that I wasn't going to be an engineer.).].

|

| I also have one of those Immunotherapy Krakens in my blood, so I guess I shouldn't be too worried about it. |

We talked for a while, because, even though we meet routinely at an appointed time to make certain I'm not actively dying, I like to think that she and I are friends. Then, suddenly, she informed me that I had graduated to six months. I was surprised, because I didn't think I'd be at six months for several years. "Nope," she said. "One year after diagnosis you go to four, and two years after you graduate to six." I went into this appointment convinced that I'd have to replay the scenario after my diagnosis where I went around telling everyone I was going to die, and that I loved them. And I came out of it not only with a clean bill of health, but with the added bonus of being considered healthy enough to last an extra two months on my own at a time.

As a young adult cancer survivor, I will never stop worrying about dying before I've lived long enough to leave my mark, to positively affect the world, and do whatever other things my mother would no doubt disapprove of. Every time I make the trip to the doctor, all of the emotions surrounding my initial diagnosis come flooding back. But in a strange, dissociated kind of way because the memories have faded, and all I really feel now is that I'm submerged underwater in a claustrophobic sea of negativity. The sensation causes me to find things that aren't there, and to worry myself into a bad place. I blame this partially on the come down from surviving cancer, the getting back to "normal." I have a wealth of experience with life and death and priorities and trivialities, intense emotions spawning from serious existential crisis, and the lessons that facing a terminal illness can teach you. But all of this fades when the tests start to come back clean, and distance begins to seep in between you and what almost prematurely ended you. In the future, I'd like to be more conscious of the divide, and learn how to better reconcile the urgency I used to feel with the humdrum of daily life. It's a lofty goal, though I'm sure it's possible. I'm not the only cancer survivor, stumbling through life trying to make sense of it all. I'm sure I'll get there. After all, I have at least six months to do it.

Photo credits: Top -- A doctor looks at an x-ray, by Ron Mahon

Labels:

Cancer,

Cancer and Fear,

Cancer Treatment,

Facing Fear,

Graduation,

Immunotherapy,

Young Adult Cancer Survivors

Thursday, October 3, 2013

Cancer Research Institute 60th Annual Awards Gala

This past Monday, September 30th, I attended the Cancer Research Institute's 60th Annual Awards Gala. The organization was nice enough to invite me and my girlfriend as guests at the event, where the leading researchers in the field of immunotherapy were assembled to discuss and receive due honors for their work. Nightline anchor and ABC News correspondent Bill Weir emceed the event, and award recipients included Dr. Bahija Jallal, executive vice president of AstraZeneca, Dr. Jill O’Donnell, CEO of the Cancer Research Institute, and Sean Parker of Napster fame. I myself was showcased at one point as a survivor, along with a few others, like Emily Whitehead, Mary Elizabeth Williams, and Sharon Belvin.

The event was held at Cipriani 42nd Street, a massive architecturally stimulating venue. Formerly the Bowery Savings Bank, the impressive space lies just across the street from the Grand Hyatt hotel and Grand Central Station, and down the block from both the Chrysler and Lincoln buildings. A huge stone archway greets visitors, ushering them into a large dining hall surrounded by modified Corinthian columns that terminates in a second archway housing an enormous rear window silhouetted by velvet curtains. Remnants of the Bowery savings Bank remain, with the dining room separated from the foyer by a framework of teller windows, and the entrance lined with deposit counters complete with pens on chains (that this writer found unpleasantly lacking in ink during an exchange of contact information).

Dinner was served in three courses, the first being a scallop salad (that I wished I could take home and love forever, and doubly enjoyed because my girlfriend doesn't like scallops), followed by filet minion or sea bass, and a rich chocolatey masterpiece that gave me four types of diabetes (how many are there?). Though I'm trying hard to keep my vegetarian ways, I even had a bite of the filet. Don't tell anyone, or I'll lose my street cred. My table was filled with fellow melanoma survivors, and we had much to discuss about the role of immunotherapy in our lives.

The musical guest, folk-rock duo Johnnyswim, came out with an appropriate mix of melodic tunes that relaxed and uplifted the crowd at the same time. Once described as “21st century troubadours,” the duo serenaded a captive audience through the entrée course with a short set. Though the acoustics at Cipriani were not optimized for the band, and at several points our table discussed the possibility that the venue chose to forego a sound check, the band spoke well enough with their sound to make up for the lack of clarity. I didn't hear a word either of them said between songs, but from the heavily reverbed noises they made that might have been words, it seemed like they were very much in tune with the event and happy for the opportunity to play the gala. Co-founder Amanda Sudano had a more personal reason to be there, as she happens to be the daughter of the late Donna Summer, who succumbed to lung cancer in 2012.

The event was a huge success, in my opinion, for many reasons, namely, 1), it encouraged ongoing research into the most promising field in oncology today: 2), it brought together the leading minds in the field for debate and discussion into the latest findings: 3), it brought together those of us who've directly benefited from immunotherapy, and provided an environment in which we felt comfortable talking to other survivors and researchers alike: and 4), because I personally haven't been to many events like it, and it was a fantastic introduction into a larger part of the cancer community.

CRI's 60th Annual Awards Gala represents the future of oncology. The most promising treatments are now coming from the field, and the organization continues to be at the forefront of a bright and hopeful future. We're getting real results due to the efforts of CRI and its donors and sponsored researchers. There are so many good things to say about the event, that it's hard to find anything negative. The strangest feeling for me occurred when I realized that I was in an environment where it was okay to be my complete self. Usually I'm holding back the survivor aspect of my character when in public, because, as a general rule, terminal illness makes people uncomfortable. I was allowed to let go at the gala, and enjoy myself in a way that I haven't in a long while, around people who genuinely understood and were trying to help, because everyone in attendance was all in this crazy world together, all working toward a common goal, whether as a survivor, researcher, donor, or in another supporting role. It enveloped me in a sense of community, and I very much hope to continue my involvement with the Cancer Research Institute's efforts in the future. If you'd like to donate to their efforts, please consider doing so here: Ways to give to CRI.

|

| Look at that handsome fellow up on the screen. |

| I felt a little like I was in the Colosseum, waiting for a lion to pop up out of the floor and try to eat me during dinner. |

The musical guest, folk-rock duo Johnnyswim, came out with an appropriate mix of melodic tunes that relaxed and uplifted the crowd at the same time. Once described as “21st century troubadours,” the duo serenaded a captive audience through the entrée course with a short set. Though the acoustics at Cipriani were not optimized for the band, and at several points our table discussed the possibility that the venue chose to forego a sound check, the band spoke well enough with their sound to make up for the lack of clarity. I didn't hear a word either of them said between songs, but from the heavily reverbed noises they made that might have been words, it seemed like they were very much in tune with the event and happy for the opportunity to play the gala. Co-founder Amanda Sudano had a more personal reason to be there, as she happens to be the daughter of the late Donna Summer, who succumbed to lung cancer in 2012.

The event was a huge success, in my opinion, for many reasons, namely, 1), it encouraged ongoing research into the most promising field in oncology today: 2), it brought together the leading minds in the field for debate and discussion into the latest findings: 3), it brought together those of us who've directly benefited from immunotherapy, and provided an environment in which we felt comfortable talking to other survivors and researchers alike: and 4), because I personally haven't been to many events like it, and it was a fantastic introduction into a larger part of the cancer community.

|

| I tried to make a deposit during the event, though all I had on me was an acute case of alcohol poisoning from the open bar. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)