It's that time of year again, when people crawl out of the woodwork shouting the failures of hundreds of years of technological advancements to the heavens. The bandwagon of mistrust in big government, big pharma, big bad doctors, and misplaced faith in big unsubstantiated opinions is about to grow three-fold like the Grinch's heart on Christmas morning. This is, after all, flu season.

The Facebook posts are running rampant: "Flu vaccine kills one boy in Texas;" "Six grandmothers in Detroit;" "Three hundred groundhogs in Montana;" "One hundred and one Arabian Nights;" and, "Twelve dancers dancing during a popular holiday sing-a-long before horrified onlookers."

Sometimes, they're framed in the form of questions designed to incite sensational reactions from the public:

"Is the flu vaccine useful?" "Does it work?" "Should we stop getting the flu shot?" "Should we stop waiting for traffic lights and wearing seat belts?" "Is eating raccoon poop really going to kill us anymore? I sprinkled some on my oatmeal this morning and I feel just fine." "Are grizzly bears suddenly the best holiday gifts for teens?"

Some of these headlines are disturbing. But make no mistake, they are all completely and unquestionably real, aside from the ones that are not.

I'm going to talk about the most common misconceptions regarding the flu vaccine, and why it's still essential that every living human do their duty to the species and get jabbed in the arm with a needle this holiday season. I will be using my unique perspective as a cancer survivor to talk about some of the immunological aspects of vaccination science. Try to relax, you may feel a little pinch.

1.) The Flu Vaccine Causes The Flu

This is completely impossible. The virus has been modified so that it's unable to proliferate and give you the flu. This is not new science, and it's been used every day for over a century. The shot form of the flu vaccine specifically doesn't even include the actual virus. It's called a subunit vaccine -- a vaccine that only contains certain parts or proteins of a virus in order to solicit an immune response to them. The nasal spray variety includes a strain of flu that's been forcibly evolved by passing it through hundreds of chick eggs in order to create a version of the disease that can't infect humans.

2.) I Always Get The Flu After Getting The Flu Vaccine

You don't (See number 1), but I can explain the reason why you might think that. Your immune system causes most symptoms you experience when you get sick -- headaches, chills, fever, nausea, aches and pains. Your body does all of that stuff to itself. A vaccine is designed to mimic a real infection, thus soliciting a real immune response. In recent years, vaccines have gotten better at diminishing side effects. Some say there shouldn't be any at all with the new rounds of flu vaccines.

Here's an anecdote. When I was going through immunotherapy, I was injecting obscene amounts of a protein called Interferon. Interferon is one of the proteins your body produces to make you feel so crappy when you get sick, and I definitely felt like I was sick all the time. That was coincidentally the year my boosters were up, and I ended up getting the flu shot, pneumonia vaccine, and the tetanus shot all at the same time. I ended up in the hospital, and after they pumped a bag of fluids into my arm, I felt a little better. Though I'm informed enough to know that the reason for this was my body's immune response to the vaccines, on top of my already overwhelmed immune system. My case was a fluke, but, subsequently, if you're currently undergoing treatment for cancer, you should consult your PCP and your oncologist to find out about side effects.

The American Cancer Society recommends that all patients get the flu shot. Read a summary of their recommendations here.

3.) Vaccines Don't Work

This is false. Edward Jenner was born in 1749. He developed an hypothesis that contracting cowpox would prevent a person from coming down with deadly smallpox. This is actually where the word vaccine originates -- from the Latin vaccinus, or, "pertaining to cows." Smallpox was eradicated from the planet in 1980. Notice how long it took to eradicate the disease from the time a solution was discovered. The reasons for this are, 1.) this was the first major step and represents the early days of vaccination science, and 2.) viruses are effing complicated. They're persistent, fast-evolving, complex organisms. Scientists have to scramble to figure out the best ways to deal with them. The flu is one of the most complicated viruses around. Seriously, look up the science, the flu is a tricky mistress. Start your research here with an article from BBC Science about the complexity of viruses and why they're so hard to beat. In the case of the flu, it's still difficult to predict which strains will run rampant each flu season with 100% accuracy, but getting the shot will offer some measure of protection regardless. And, to be fair to smallpox research, a campaign to globally eliminate the disease wasn't undertaken until 1959. If you're interested, you can read more about the history of the disease and its eradication here.

And here's a nifty bulletin from the WHO providing stats and figures for the successful use of vaccines, including the fact that in the U.S., incidence of infection from the nine diseases recommended for vaccination has decreased by 99%.

4.) Vaccines Contain Terrible, Awful, No Good, Very Bad Ingredients

The most commonly-cited ingredients of the flu vaccine are mercury and formaldehyde. Okay, let's talk a little about chemistry for a moment. Mercury is an element. It can be found in different chemicals and substances, just like any other element. The ingredient in question is called thimerosal, which breaks down into ethylmercury. Ethylmercury is a substance that metabolizes quickly and exits the body without causing a toxic build-up of mercury. Again, this is the type found in vaccines in the form of the preservative, thimerosal. The dangerous sort, methylmercury, bio-accumulates through the food chain and can build up in the body through dietary intake, and create all sorts of risk factors to an individual's health. This is why women aren't supposed to eat certain fish while pregnant -- the kind like shark and swordfish that are at the top of the food chain, because they'll have high concentrations of mercury coursing through them due to all the lower inhabitants of the food chain also consuming methylmercury. Environmental contamination of mercury is also a factor in choosing your fish. If you don't care much for facts and still like the idea of having mercury in your shot regardless, you can ask to have one without thimerosal in it.

Formaldehyde is an organic chemical that occurs naturally in the body. But, like most everything else, too much of it can be a bad thing. It's produced internally, and we ingest it daily through our diet and other means, like breathing. Formaldehyde is everywhere. Though, it also metabolizes quickly, and doesn't easily accumulate. The fact is, you get more formaldehyde by eating a pear than you do from the flu vaccine. Here's a convenient guide. Highlights to keep in mind: the most formaldehyde you'll probably get from vaccines will come when you're a baby, at the six-month checkup, and the amount will be 160 times less than the amount naturally produced by your body every single day.

There are other ingredients cited, and they all have equally reasonable and mundane chemical explanations. Why not do some reading?

5.) My Decision To Abstain From Getting Vaccinated Doesn't Hurt You

This is a reasonable thing to think. Because, what you do is your business, right? Well, not in the case of public health. It turns out, there's a thing called Community Immunity, or (an even sillier though less poetic name) Herd Immunity. Herd Immunity is a state or condition that's met when a sufficient amount of the population is immunized against a given disease, cited around 75-95%, though it varies for specific diseases. Herd Immunity provides a safety net for society, and allows us to successfully contain a virus. If you don't get vaccinated, you're running a cost-benefit analysis and playing a fun casino home-game. Only when you lose, the risks may be a little higher than you bargained for, and include the extermination of the human race. By not getting inoculated, you're providing a medium for the flu to evolve and become even harder to beat. Herd Immunity is a complex science, and you can read more about it here.

There you have it. Those are the top flu myths around, and, conveniently, my own personal favorites. There are many other false claims and misconceptions about the flu vaccine, such as, they cause autism, asthma, allergies, Alzheimer's, narcolepsy, blood disorders, the starving of puppies, your parents' divorce, and that they're descended directly from an intimate meeting between Satan and all those Hugo Weaving characters from Cloud Atlas. I won't go into these, because there is absolutely no clinical research to show that there is merit to any of them, and a whole lot of research that says they're bunk.

Parting tip: Always be wary of claims suggesting the rise in a certain disease or condition is dependent on any man-made means -- the rise of rates is proportional to the rise in population (i.e. there are more people, so there will be more cases of X). Make sure to do your own research and be your own advocate, but, at the same time, pay attention to the actual research. Facts are important.

There are other flu vaccine guides out there on the interwebs, including this one from Gizmodo, which is extremely thorough and comprehensive.

Tuesday, December 24, 2013

Friday, December 20, 2013

My Cancer Brings All the Crazies to the Yard

In today's day and age, it's important for the patient to be his or her own advocate. It's an unfortunate reality, but as soon as something happens to you, you've unwittingly opened yourself to an entirely new world that you may not be prepared to successfully navigate. And, while doing your best to focus on the issue at hand, it's easy to be taken in by snake oil and pseudoscience. There's nothing worse than a cancer opportunist -- someone who uses your illness to his or her advantage, pushing ineffective and sometimes dangerous products and treatments. I talk about some of my favorite fake treatments in another post, The Dangers of Alternative Health: 3 Treatments That Can Cause Some Serious Damage.

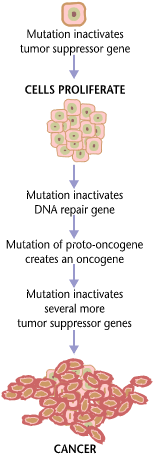

The thing about cancer is that it's a biological process -- several, in fact, occurring simultaneously. Cancer is a series of genetic and epigenetic malfunctions. It isn't caused by any solitary force. And it certainly isn't caused by mysterious "toxins" with no names or identities. It isn't caused by your attitude either, or your karma (by the way, the western definition of karma is not even entirely accurate), or even when your room mate peed in the mini fridge in your dorm room the night he was really drunk.

Having cancer is a desperate situation for many people. And it brings out the best and worst of the human race. There are several reasons to be wary of anyone who tries to sell you something when you need it most. The sad fact is that many people fall prey to these villains, foregoing entry into legitimate treatment programs and significantly decreasing their odds of survival.

The first and most important line of defense is to do your research. In today's culture, fact-checking has become a long-forgotten practice. Claims are made, and whoever yells the loudest is always declared the most honest. That's not how science works, unfortunately. In the real world, experts propose hypotheses and test them until they can be fully evaluated and verified. And, as Neil deGrasse Tyson put it, "The good thing about science is that it's true whether or not you believe in it."

For whatever reason, the age of information has had the opposite effect of informing the public. It could be that with all of this information at hand, it makes it easier for people to believe that they know much more about a particular issue than they really do. It still takes years of schooling to become an expert in a given field, like oncology. The danger arises among those who falsely profess a knowledge of healthcare and push miracle cures on the public that only they have uncovered through collecting pee from public parks, or shooting coffee into your rectum. It's not easy to determine whether or not modern snake oil salesmen peddle their wares with the intention of making money from their faulty products, or if they genuinely think what they're doing will provide some benefit. I tend to believe the former in most cases. The current state of healthcare in America reminds me of my favorite quote by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov: "Anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that 'my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.'"

All of these alternative therapies will bankrupt you, because they're obscenely expensive and your insurance won't pay for them, because they aren't medicine. Mainstream healthcare is also extremely expensive, to be fair, and the U.S. is by far the most expensive nation in which to get sick. But there is a mechanism in place to at least ensure that a patient can find treatment backed by real medical science. If you aren't sure how to find out whether or not a treatment is bogus, just look for the clinical research. Real treatments are published, peer-reviewed, and independently verified over a number of years in order to ensure their safety and effectiveness. Cancer is tricky, because we can't at this point cure it, and that scares many people into thinking that's because traditional treatments don't work, when really it's just the best we can do at this point. With the advent of new immunotherapy research, results and patient outcomes are looking even more promising these days, and we can expect a new wave of even more effective treatments very soon. Human innovation is a process. Yes, people are greedy, and things still cost money. But the most villainous and greedy among us are the opportunists who take advantage of the desperation of others.

The thing about cancer is that it's a biological process -- several, in fact, occurring simultaneously. Cancer is a series of genetic and epigenetic malfunctions. It isn't caused by any solitary force. And it certainly isn't caused by mysterious "toxins" with no names or identities. It isn't caused by your attitude either, or your karma (by the way, the western definition of karma is not even entirely accurate), or even when your room mate peed in the mini fridge in your dorm room the night he was really drunk.

|

| The process looks like this. |

The first and most important line of defense is to do your research. In today's culture, fact-checking has become a long-forgotten practice. Claims are made, and whoever yells the loudest is always declared the most honest. That's not how science works, unfortunately. In the real world, experts propose hypotheses and test them until they can be fully evaluated and verified. And, as Neil deGrasse Tyson put it, "The good thing about science is that it's true whether or not you believe in it."

For whatever reason, the age of information has had the opposite effect of informing the public. It could be that with all of this information at hand, it makes it easier for people to believe that they know much more about a particular issue than they really do. It still takes years of schooling to become an expert in a given field, like oncology. The danger arises among those who falsely profess a knowledge of healthcare and push miracle cures on the public that only they have uncovered through collecting pee from public parks, or shooting coffee into your rectum. It's not easy to determine whether or not modern snake oil salesmen peddle their wares with the intention of making money from their faulty products, or if they genuinely think what they're doing will provide some benefit. I tend to believe the former in most cases. The current state of healthcare in America reminds me of my favorite quote by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov: "Anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that 'my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.'"

All of these alternative therapies will bankrupt you, because they're obscenely expensive and your insurance won't pay for them, because they aren't medicine. Mainstream healthcare is also extremely expensive, to be fair, and the U.S. is by far the most expensive nation in which to get sick. But there is a mechanism in place to at least ensure that a patient can find treatment backed by real medical science. If you aren't sure how to find out whether or not a treatment is bogus, just look for the clinical research. Real treatments are published, peer-reviewed, and independently verified over a number of years in order to ensure their safety and effectiveness. Cancer is tricky, because we can't at this point cure it, and that scares many people into thinking that's because traditional treatments don't work, when really it's just the best we can do at this point. With the advent of new immunotherapy research, results and patient outcomes are looking even more promising these days, and we can expect a new wave of even more effective treatments very soon. Human innovation is a process. Yes, people are greedy, and things still cost money. But the most villainous and greedy among us are the opportunists who take advantage of the desperation of others.

Labels:

Alternative Medicine,

Cancer,

Healthcare,

Immunotherapy,

Isaac Asimov,

Neil deGrasse Tyson,

Science

Fifty Shades of Kevin: A Dramatic Reading

My friends and I have been renting a cabin at Cook Forest in Clarion for the past few summers. We stay for a long weekend, and get into as much trouble as we possibly can. The first year we went, I was undergoing immunotherapy treatment for stage 3 melanoma, and I was shocked at how much fun I had despite the side effects. The fatigue and other symptoms were mostly forgotten, and for the most part I could keep up with the festivities. This year, we were at it again. It just so happened that this time around one of our friends brought along a copy of 50 Shades. Since none of us have age-appropriate maturity levels, we couldn't help but to pass the book around for dramatic readings. Mine starts off in Standard American i.e. Shakespeare, and quickly deteriorates into a bad Dustin Hoffman from Hook. Watch my personal interpretation of a passage from the book below.

Thursday, December 19, 2013

Bloggers Unite! Post Your URL's Here

So, I just transferred my blog to my Google+ account, which turned out to be a huge pain. And, in the end, I lost all the blogs I was following. I'd like to reconnect with all of you, so if you could, please comment with your blog and URL on this post. I want to bring together a better sense of community to discuss issues in the area of young adult cancer, cancer, and the state of healthcare in general. Let's all band together, and we can start by following each other and lending our support.

P.S. I feel like this is today's equivalent of dropping my phone in the sink and losing all my contact info. Oh, first-world problems. Even so, I think good things could come from it, including a better sense of togetherness.

Photo Credits: Top -- Joris Louwes via Flickr; Bottom -- Robbert van der Steeg via Flickr

P.S. I feel like this is today's equivalent of dropping my phone in the sink and losing all my contact info. Oh, first-world problems. Even so, I think good things could come from it, including a better sense of togetherness.

|

| We can do it, just like some kind of weird elephant orgy. |

Photo Credits: Top -- Joris Louwes via Flickr; Bottom -- Robbert van der Steeg via Flickr

Wednesday, December 11, 2013

Holiday Cheer, With A Little Death Mixed In

I realize I would have thrown up this morning, had I let myself. This morning, all of last night, and probably all of yesterday had I not been occupying my time playing video games. My mother came down at eleven to say goodnight. “Are you going to bed?” she asked. I told her I would. “Are you worried?” she asked. I blew up in her face, because I’d been marathon-ing Skyrim precisely so I wouldn’t have to think about how worried I was. It was some time before we were able to settle the issue and she went to bed.

This morning was six days after the stuffing, the cranberry sauce, the turkey coma, and the mashed potatoes with the butter poured in the middle to dip in. Six days after I’d made all the pies: an apple, a pumpkin, an apple dumpling, and a mighty scrumptious pumpkin cheesecake. I’m still home for the holiday. My girlfriend left on Sunday, and I wasn’t able to go with her. We found a mass Wednesday night, just before Thanksgiving. I had been diagnosed with cancer in 2011 at the age of 25, so I kept my potential recurrence to myself through the holiday, since I’d seen the effects of this kind of news firsthand, and I didn’t want to ruin the festivities for everyone.

This morning was also four days after the champagne toast my mother arranged to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the completion of my cancer treatment. “What’s the best kind of champagne?” she’d asked me just days before. “Can you get some cheap?” I’d learned from a college roommate that Korbel was the best cheap champagne and I told her so. I immediately knew something was up, because she only asks me questions like that when she’s getting me something. And I couldn’t for the life of me figure out why she would be getting me champagne. Cancer was that far from my mind. Then I found the mass, and I had felt like a fraud, clinking glasses, smiling around the table, knowing full-well that I might once again be actively dying.

No matter the outcome of the poking and prodding that was to come, I was once again faced with the knowledge that I had had cancer, and that I’d had three surgeries and an awful, year-long treatment to prevent it from coming back, all in my mid-twenties. And that being so young, I had significant reason to think it might rear its ugly head sometime down the long road ahead.

There was a New York Times article about this over the summer. The quoted findings, from Dr. Alex J. Mitchell at the University of Leicester, stated that 18% of young adults remain severely anxious about their experience with cancer two to ten years after being diagnosed. In couples, that number rose to 28%, with 40% of spouses reporting above-average levels. The anxiety is real. I feel the complete set of fears rise up in my neck, the pain of every hair on my body standing sharply at attention, whenever I think I might have found something suspicious poking out. And that will never change. I feel guilty every day because I’m in a happy, healthy relationship with someone I truly care about, and what all this must mean for her.

Studies also suggest the same is true of depression, though I’ve personally avoided the brunt of that. Aside from a stint with chemical depression induced by my immunotherapy treatment, I’ve been my father’s son -- an unfailing optimist. When I was first diagnosed, and during the ensuing year of treatment, which some refer to with such cavalier terms as “battle,” “struggle,” or some other equally obnoxious buzzword, I went to therapy regularly to work through a healthy episode of PTSD. According to a study done by Dr. Mary Rourke at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, I’m not alone there either. By evaluating one hundred eighty-two survivors of pediatric cancers, she found that 16% had PTSD. Dr. Rourke concluded that young adult cancer survivors experience more psychological problems than the general population.

It’s no wonder then, sitting over my healthy serving of dark meat, watching my family laugh and drink, watching my girlfriend for any obvious signs of hating my family, that I felt a sense of dread underneath it all. What if I don’t have many more occasions like this? No more holidays, no more fun times with the family, no more hoping my girlfriend will get along with the craziest, most inappropriate members of my clan. Looking around the table at the smiling faces, I asked myself, what if I don’t have any more holidays at all?

This morning I had an ultrasound at the local hospital in town. My family doctor doesn’t have the little stick thingy or the gel at his office, so they made me wait while the hospital took forever to schedule an appointment for today. To my (pseudo) relief, the tech didn’t see anything unusual. My Physician Assistant best friend reminds me that techs are not doctors, and the official results are still pending. I am not fully relieved, nor will I ever be.

I am now 28 years old, and this is what I’ll be doing for the rest of my life. I love my family, and my friends, and I hope to have a long, prosperous life in a career that satisfies me, with a partner by my side who complements me and fills me with joy. There is a dark cloud that lingers above me, threatening to take it all away at a moment’s notice. I willingly pay it no mind when it’s unreasonable to do so, but that only means that when I have a legitimate scare, it comes back in full force. It took a long time to come to terms with this pattern, but I realize that it will always be a force in my life. Only at times like Thanksgiving, when I can sit around a table with the people who are most important, laugh, play games, and drink cheap champagne, that I realize how lucky I am to have had any of it at all.

This morning was six days after the stuffing, the cranberry sauce, the turkey coma, and the mashed potatoes with the butter poured in the middle to dip in. Six days after I’d made all the pies: an apple, a pumpkin, an apple dumpling, and a mighty scrumptious pumpkin cheesecake. I’m still home for the holiday. My girlfriend left on Sunday, and I wasn’t able to go with her. We found a mass Wednesday night, just before Thanksgiving. I had been diagnosed with cancer in 2011 at the age of 25, so I kept my potential recurrence to myself through the holiday, since I’d seen the effects of this kind of news firsthand, and I didn’t want to ruin the festivities for everyone.

This morning was also four days after the champagne toast my mother arranged to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the completion of my cancer treatment. “What’s the best kind of champagne?” she’d asked me just days before. “Can you get some cheap?” I’d learned from a college roommate that Korbel was the best cheap champagne and I told her so. I immediately knew something was up, because she only asks me questions like that when she’s getting me something. And I couldn’t for the life of me figure out why she would be getting me champagne. Cancer was that far from my mind. Then I found the mass, and I had felt like a fraud, clinking glasses, smiling around the table, knowing full-well that I might once again be actively dying.

No matter the outcome of the poking and prodding that was to come, I was once again faced with the knowledge that I had had cancer, and that I’d had three surgeries and an awful, year-long treatment to prevent it from coming back, all in my mid-twenties. And that being so young, I had significant reason to think it might rear its ugly head sometime down the long road ahead.

There was a New York Times article about this over the summer. The quoted findings, from Dr. Alex J. Mitchell at the University of Leicester, stated that 18% of young adults remain severely anxious about their experience with cancer two to ten years after being diagnosed. In couples, that number rose to 28%, with 40% of spouses reporting above-average levels. The anxiety is real. I feel the complete set of fears rise up in my neck, the pain of every hair on my body standing sharply at attention, whenever I think I might have found something suspicious poking out. And that will never change. I feel guilty every day because I’m in a happy, healthy relationship with someone I truly care about, and what all this must mean for her.

Studies also suggest the same is true of depression, though I’ve personally avoided the brunt of that. Aside from a stint with chemical depression induced by my immunotherapy treatment, I’ve been my father’s son -- an unfailing optimist. When I was first diagnosed, and during the ensuing year of treatment, which some refer to with such cavalier terms as “battle,” “struggle,” or some other equally obnoxious buzzword, I went to therapy regularly to work through a healthy episode of PTSD. According to a study done by Dr. Mary Rourke at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, I’m not alone there either. By evaluating one hundred eighty-two survivors of pediatric cancers, she found that 16% had PTSD. Dr. Rourke concluded that young adult cancer survivors experience more psychological problems than the general population.

It’s no wonder then, sitting over my healthy serving of dark meat, watching my family laugh and drink, watching my girlfriend for any obvious signs of hating my family, that I felt a sense of dread underneath it all. What if I don’t have many more occasions like this? No more holidays, no more fun times with the family, no more hoping my girlfriend will get along with the craziest, most inappropriate members of my clan. Looking around the table at the smiling faces, I asked myself, what if I don’t have any more holidays at all?

This morning I had an ultrasound at the local hospital in town. My family doctor doesn’t have the little stick thingy or the gel at his office, so they made me wait while the hospital took forever to schedule an appointment for today. To my (pseudo) relief, the tech didn’t see anything unusual. My Physician Assistant best friend reminds me that techs are not doctors, and the official results are still pending. I am not fully relieved, nor will I ever be.

I am now 28 years old, and this is what I’ll be doing for the rest of my life. I love my family, and my friends, and I hope to have a long, prosperous life in a career that satisfies me, with a partner by my side who complements me and fills me with joy. There is a dark cloud that lingers above me, threatening to take it all away at a moment’s notice. I willingly pay it no mind when it’s unreasonable to do so, but that only means that when I have a legitimate scare, it comes back in full force. It took a long time to come to terms with this pattern, but I realize that it will always be a force in my life. Only at times like Thanksgiving, when I can sit around a table with the people who are most important, laugh, play games, and drink cheap champagne, that I realize how lucky I am to have had any of it at all.

Labels:

Anxiety,

Cancer,

Depression,

Holidays,

Immunotherapy,

Young Adult Cancer Survivors

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Another October Down, Yet Cancer's Still Around

Now that another October is in the books, the pink's all been stuffed away and will be gathering dust until fall of next year. While October's awareness campaigns are important, it's equally important to remember a few key points.

1.) Pinkwashing is still a huge problem. Make sure to do your homework. A lot of organizations flash the pink and expect you not to ask questions. There's a lot of questionable people out there who engage in questionable business practices. Be careful and pay attention. Be certain you're donating to a cause, and that the majority of your money is going to said cause, and isn't serving to inflate someone's wallet instead. This is true of all charitable donations. Charity Navigator is a great resource that can help you find out which organizations are worthy of your money. And there are resources available that deal specifically with pinkwashing, like Think Before You Pink.

2.) Even legitimate fundraising attempts don't always target the right areas. Fighting breast cancer is a great cause, but as others have pointed out, the funds raised in October overwhelmingly go toward funding prevention and treatment for those in low-risk categories, and leave the majority of patients high and dry. Metastatic disease benefits only marginally from the month's fundraising campaigns, which isn't the most logical, since metastasis is what actually kills people.

3.) Cancer doesn't end with breast cancer. Here's a fact that I'll bet most people don't know: lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths in women. In fact, lung cancer is responsible for the deaths of more women annually than breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and uterine cancer combined. While I'm happy to report that breast cancer is pulling in tremendous support from all corners, it's upsetting to realize this fact, and even more upsetting to have to point it out. Cancer really shouldn't be so isolationist. It's important to create an atmosphere where all of us have the same access to treatment, support, and the benefits of extensive fundraising campaigns.

Cancer sucks, period. It destroys lives, rips apart families, and takes people for the proverbial ride. It's a disgusting truth that there are those in the world who would use it for personal gain. But it's happening, and awareness months are no exception. Be vigilant when donating, and know that it's worth the extra fifteen minutes to research the facts behind the cause. At the very least, look for infographics that provide financial breakdowns like this one from the American Cancer Society.

Happy donating, and let's kick cancer's ass all year-round.

Image credits: Middle -- Leading Cause of Cancer Deaths (2007), via Junk Charts; Bottom -- Where Does Your Money Go? via the American Cancer Society.

Friday, October 11, 2013

Graduation Day: Dying From Cancer To Clean Scans In One Easy Step

I had my checkup at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center recently. In the days leading up to the appointment, I was, as always, irrationally paranoid about every bump and bruise and utterly convinced that I had only days left to live. "What the hell is that??" I'd say in the shower, only to find that the offending lump was in fact some completely normal anatomical part that was supposed to be where it was and had been for the prior 28 years of my life. One day I found something really large that turned out to be my bicep. Is it supposed to feel like that?? Jesus.

I'm pretty convinced that I also manufactured a crisis by feeling up the nodes in my thigh so much that I bruised the area around my junk, causing me to worry about the "strange sensation" so much that I began to formulate my last goodbyes and figure out who I should give my surplus of Magic cards to (they aren't even legal to play anymore, but what did you expect from a young adult cancer survivor -- a current deck of Magic cards? What, am I made of money?). At the appointment, the PA noticed similar bruising in the nodes between my armpit and chest, which had previously been described to me as "bumpy." It was at this point I wondered if I could actually give myself cancer from checking so hard for signs of cancer. Or at the very least, a severe case of internal bleeding. Then I thought of the scenes from every medical drama in history where the doctor comes out and says very sadly, "I'm sorry, we can't stop the bleeding." And I think to myself, Wait, what? Don't you have like science and bags of other people's blood and stuff like that? I mean, wrap it in a t-shirt for God's sake. And I think of how much I would really disapprove of being the subject of one of those scenes because I pressed too hard while checking my nodes.

I did my X-Ray, blood work, and obligatory waiting room meditation before they called me back and stripped me down. I met a new PA student who checked me over and wanted to talk about what I was doing in life, and all the bizarrely existential things people say to one another with eerie lightness during an initial meeting, and all I could think about was how bumpy my nodes were. I stumbled through the conversation until the regular PA came in, who I'm very comfortable with and who has made this whole close to death thing a little less crappy. As it turns out, all my worrying was for nothing (isn't it always? Worrying is, by its very nature, useless). The X-Ray was clear, which meant my core was not filled with death, and the blood work confirmed that, yes, my blood was mostly made of blood, and not terrifying cancer Legos waiting to combine into a macabre pirate ship and sail right into my brain (though the castle Legos were my favorite [and I always made my mother buy them for Christmas and then put them together for me. It was obvious at an early age that I wasn't going to be an engineer.).].

We talked for a while, because, even though we meet routinely at an appointed time to make certain I'm not actively dying, I like to think that she and I are friends. Then, suddenly, she informed me that I had graduated to six months. I was surprised, because I didn't think I'd be at six months for several years. "Nope," she said. "One year after diagnosis you go to four, and two years after you graduate to six." I went into this appointment convinced that I'd have to replay the scenario after my diagnosis where I went around telling everyone I was going to die, and that I loved them. And I came out of it not only with a clean bill of health, but with the added bonus of being considered healthy enough to last an extra two months on my own at a time.

As a young adult cancer survivor, I will never stop worrying about dying before I've lived long enough to leave my mark, to positively affect the world, and do whatever other things my mother would no doubt disapprove of. Every time I make the trip to the doctor, all of the emotions surrounding my initial diagnosis come flooding back. But in a strange, dissociated kind of way because the memories have faded, and all I really feel now is that I'm submerged underwater in a claustrophobic sea of negativity. The sensation causes me to find things that aren't there, and to worry myself into a bad place. I blame this partially on the come down from surviving cancer, the getting back to "normal." I have a wealth of experience with life and death and priorities and trivialities, intense emotions spawning from serious existential crisis, and the lessons that facing a terminal illness can teach you. But all of this fades when the tests start to come back clean, and distance begins to seep in between you and what almost prematurely ended you. In the future, I'd like to be more conscious of the divide, and learn how to better reconcile the urgency I used to feel with the humdrum of daily life. It's a lofty goal, though I'm sure it's possible. I'm not the only cancer survivor, stumbling through life trying to make sense of it all. I'm sure I'll get there. After all, I have at least six months to do it.

Photo credits: Top -- A doctor looks at an x-ray, by Ron Mahon

I'm pretty convinced that I also manufactured a crisis by feeling up the nodes in my thigh so much that I bruised the area around my junk, causing me to worry about the "strange sensation" so much that I began to formulate my last goodbyes and figure out who I should give my surplus of Magic cards to (they aren't even legal to play anymore, but what did you expect from a young adult cancer survivor -- a current deck of Magic cards? What, am I made of money?). At the appointment, the PA noticed similar bruising in the nodes between my armpit and chest, which had previously been described to me as "bumpy." It was at this point I wondered if I could actually give myself cancer from checking so hard for signs of cancer. Or at the very least, a severe case of internal bleeding. Then I thought of the scenes from every medical drama in history where the doctor comes out and says very sadly, "I'm sorry, we can't stop the bleeding." And I think to myself, Wait, what? Don't you have like science and bags of other people's blood and stuff like that? I mean, wrap it in a t-shirt for God's sake. And I think of how much I would really disapprove of being the subject of one of those scenes because I pressed too hard while checking my nodes.

|

| "I've taken out half of your bones and hung them on this pole here, and from these scans it looks like all of your blood has come with it. I've done everything I can." |

I did my X-Ray, blood work, and obligatory waiting room meditation before they called me back and stripped me down. I met a new PA student who checked me over and wanted to talk about what I was doing in life, and all the bizarrely existential things people say to one another with eerie lightness during an initial meeting, and all I could think about was how bumpy my nodes were. I stumbled through the conversation until the regular PA came in, who I'm very comfortable with and who has made this whole close to death thing a little less crappy. As it turns out, all my worrying was for nothing (isn't it always? Worrying is, by its very nature, useless). The X-Ray was clear, which meant my core was not filled with death, and the blood work confirmed that, yes, my blood was mostly made of blood, and not terrifying cancer Legos waiting to combine into a macabre pirate ship and sail right into my brain (though the castle Legos were my favorite [and I always made my mother buy them for Christmas and then put them together for me. It was obvious at an early age that I wasn't going to be an engineer.).].

|

| I also have one of those Immunotherapy Krakens in my blood, so I guess I shouldn't be too worried about it. |

We talked for a while, because, even though we meet routinely at an appointed time to make certain I'm not actively dying, I like to think that she and I are friends. Then, suddenly, she informed me that I had graduated to six months. I was surprised, because I didn't think I'd be at six months for several years. "Nope," she said. "One year after diagnosis you go to four, and two years after you graduate to six." I went into this appointment convinced that I'd have to replay the scenario after my diagnosis where I went around telling everyone I was going to die, and that I loved them. And I came out of it not only with a clean bill of health, but with the added bonus of being considered healthy enough to last an extra two months on my own at a time.

As a young adult cancer survivor, I will never stop worrying about dying before I've lived long enough to leave my mark, to positively affect the world, and do whatever other things my mother would no doubt disapprove of. Every time I make the trip to the doctor, all of the emotions surrounding my initial diagnosis come flooding back. But in a strange, dissociated kind of way because the memories have faded, and all I really feel now is that I'm submerged underwater in a claustrophobic sea of negativity. The sensation causes me to find things that aren't there, and to worry myself into a bad place. I blame this partially on the come down from surviving cancer, the getting back to "normal." I have a wealth of experience with life and death and priorities and trivialities, intense emotions spawning from serious existential crisis, and the lessons that facing a terminal illness can teach you. But all of this fades when the tests start to come back clean, and distance begins to seep in between you and what almost prematurely ended you. In the future, I'd like to be more conscious of the divide, and learn how to better reconcile the urgency I used to feel with the humdrum of daily life. It's a lofty goal, though I'm sure it's possible. I'm not the only cancer survivor, stumbling through life trying to make sense of it all. I'm sure I'll get there. After all, I have at least six months to do it.

Photo credits: Top -- A doctor looks at an x-ray, by Ron Mahon

Labels:

Cancer,

Cancer and Fear,

Cancer Treatment,

Facing Fear,

Graduation,

Immunotherapy,

Young Adult Cancer Survivors

Thursday, October 3, 2013

Cancer Research Institute 60th Annual Awards Gala

This past Monday, September 30th, I attended the Cancer Research Institute's 60th Annual Awards Gala. The organization was nice enough to invite me and my girlfriend as guests at the event, where the leading researchers in the field of immunotherapy were assembled to discuss and receive due honors for their work. Nightline anchor and ABC News correspondent Bill Weir emceed the event, and award recipients included Dr. Bahija Jallal, executive vice president of AstraZeneca, Dr. Jill O’Donnell, CEO of the Cancer Research Institute, and Sean Parker of Napster fame. I myself was showcased at one point as a survivor, along with a few others, like Emily Whitehead, Mary Elizabeth Williams, and Sharon Belvin.

The event was held at Cipriani 42nd Street, a massive architecturally stimulating venue. Formerly the Bowery Savings Bank, the impressive space lies just across the street from the Grand Hyatt hotel and Grand Central Station, and down the block from both the Chrysler and Lincoln buildings. A huge stone archway greets visitors, ushering them into a large dining hall surrounded by modified Corinthian columns that terminates in a second archway housing an enormous rear window silhouetted by velvet curtains. Remnants of the Bowery savings Bank remain, with the dining room separated from the foyer by a framework of teller windows, and the entrance lined with deposit counters complete with pens on chains (that this writer found unpleasantly lacking in ink during an exchange of contact information).

Dinner was served in three courses, the first being a scallop salad (that I wished I could take home and love forever, and doubly enjoyed because my girlfriend doesn't like scallops), followed by filet minion or sea bass, and a rich chocolatey masterpiece that gave me four types of diabetes (how many are there?). Though I'm trying hard to keep my vegetarian ways, I even had a bite of the filet. Don't tell anyone, or I'll lose my street cred. My table was filled with fellow melanoma survivors, and we had much to discuss about the role of immunotherapy in our lives.

The musical guest, folk-rock duo Johnnyswim, came out with an appropriate mix of melodic tunes that relaxed and uplifted the crowd at the same time. Once described as “21st century troubadours,” the duo serenaded a captive audience through the entrée course with a short set. Though the acoustics at Cipriani were not optimized for the band, and at several points our table discussed the possibility that the venue chose to forego a sound check, the band spoke well enough with their sound to make up for the lack of clarity. I didn't hear a word either of them said between songs, but from the heavily reverbed noises they made that might have been words, it seemed like they were very much in tune with the event and happy for the opportunity to play the gala. Co-founder Amanda Sudano had a more personal reason to be there, as she happens to be the daughter of the late Donna Summer, who succumbed to lung cancer in 2012.

The event was a huge success, in my opinion, for many reasons, namely, 1), it encouraged ongoing research into the most promising field in oncology today: 2), it brought together the leading minds in the field for debate and discussion into the latest findings: 3), it brought together those of us who've directly benefited from immunotherapy, and provided an environment in which we felt comfortable talking to other survivors and researchers alike: and 4), because I personally haven't been to many events like it, and it was a fantastic introduction into a larger part of the cancer community.

CRI's 60th Annual Awards Gala represents the future of oncology. The most promising treatments are now coming from the field, and the organization continues to be at the forefront of a bright and hopeful future. We're getting real results due to the efforts of CRI and its donors and sponsored researchers. There are so many good things to say about the event, that it's hard to find anything negative. The strangest feeling for me occurred when I realized that I was in an environment where it was okay to be my complete self. Usually I'm holding back the survivor aspect of my character when in public, because, as a general rule, terminal illness makes people uncomfortable. I was allowed to let go at the gala, and enjoy myself in a way that I haven't in a long while, around people who genuinely understood and were trying to help, because everyone in attendance was all in this crazy world together, all working toward a common goal, whether as a survivor, researcher, donor, or in another supporting role. It enveloped me in a sense of community, and I very much hope to continue my involvement with the Cancer Research Institute's efforts in the future. If you'd like to donate to their efforts, please consider doing so here: Ways to give to CRI.

|

| Look at that handsome fellow up on the screen. |

| I felt a little like I was in the Colosseum, waiting for a lion to pop up out of the floor and try to eat me during dinner. |

The musical guest, folk-rock duo Johnnyswim, came out with an appropriate mix of melodic tunes that relaxed and uplifted the crowd at the same time. Once described as “21st century troubadours,” the duo serenaded a captive audience through the entrée course with a short set. Though the acoustics at Cipriani were not optimized for the band, and at several points our table discussed the possibility that the venue chose to forego a sound check, the band spoke well enough with their sound to make up for the lack of clarity. I didn't hear a word either of them said between songs, but from the heavily reverbed noises they made that might have been words, it seemed like they were very much in tune with the event and happy for the opportunity to play the gala. Co-founder Amanda Sudano had a more personal reason to be there, as she happens to be the daughter of the late Donna Summer, who succumbed to lung cancer in 2012.

The event was a huge success, in my opinion, for many reasons, namely, 1), it encouraged ongoing research into the most promising field in oncology today: 2), it brought together the leading minds in the field for debate and discussion into the latest findings: 3), it brought together those of us who've directly benefited from immunotherapy, and provided an environment in which we felt comfortable talking to other survivors and researchers alike: and 4), because I personally haven't been to many events like it, and it was a fantastic introduction into a larger part of the cancer community.

|

| I tried to make a deposit during the event, though all I had on me was an acute case of alcohol poisoning from the open bar. |

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Happy Birthday! Tales Of An Aging Cancer Survivor

My birthday is coming up. It'll be the first birthday I've had since treatment ended. My birthday, my birthday, my birthday. I suddenly can't stop saying the words. Soon, I'll be officially one year older. Bring on the years, I say. The looming shadow of untimely death may still follow doggedly at my heels, but it's less and less relevant. Like an aging pop star, grasping for attention in the tabloids by snorting things and banging things and hanging other things out windows. Such is the state of my conscious thoughts on the subject of the decay of my physical viscera.

All thugs and chumps must inevitably grow up. But not all thugs and chumps must like it. This one does.

|

| Birthdays attract bears. |

To be honest, I haven't thought much about it until I was reminded of the approaching date. And then, I didn't care enough to really process the information until I sat down to write this post. Now I can't stop myself from feeling elated at the prospect of the number of years I've been on this Earth getting, well, more numerous. So it is with complete and utter childlike eagerness that I say, more numerous numbers please! May they grow and grow, until a harvest of numbers shall be laid out in a banquet of the wealth of my years, garnished with the love of those I hold dear.

|

| If Dad tries to eat all of my cake again this year... |

Sorry about that last part. I get all sentimental when I think about not dying and instead spending the time I could have spent dead with the people in my life that I like the best. It's a simple thing, really. But often overlooked among the day-to-day. Most people dread this birthday stuff -- I used to. I never wanted to make a big deal of it, and I didn't want to remind myself that I was chipping away at my youth, just by standing back and watching the sands filter through. Age is something we can't control, and getting older is mostly terrifying. It seems almost like a punishment. Dealt to us for no apparent reason, and without just cause. What have we done to deserve these advancing years? These days, I ask the same question, but with a very different twist. What have I done to deserve another birthday?

Image credits: Top -- HAPPY BIRTHDAY, by ritchielee via flickr; Middle -- Cleveland Zoo's birthday party, by Yvonne via flickr; Bottom -- murder on birthday 3, by Murat Suyur via deviantART

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

How Would You Want To Die?

Today I tripped over my total gym while moving to a new exercise and caught myself awkwardly before face planting and spilling my brains on the floor. Then, after the workout, I slipped in the shower, bouncing on one foot to keep myself from falling (which is something I always do when I slip in the shower that makes next to no sense, because if you slip with the other foot, you have nothing left to save you and will surely die). I sprayed my new leather shoes this morning, reading on the back of the label that the chemicals "can cause flash fires," and I day dreamed about being swallowed in a cloud of fiery death.

I got to thinking very quickly, in this maze of macabre disaster I call a home, about how I'd actually like to go out. Having survived cancer already, I have conflicting opinions on the subject. After surviving a life-threatening tragedy, you don't particularly want to go out in just any lame, regular sort of way. You want some even more intense option, like drowning after saving everyone you love from a sinking battleship, or fighting off an alien invasion.

Other people are also aware of this fact. I was crossing the street the other day with my friend Darrell, and when we got into the bus lane he held out his hand and said, "Watch out for buses. You don't want to be run over by a bus after you lived through cancer." And I'd say that's pretty accurate.

On the other hand, after surviving a horrible, traumatizing disease, it's easy to want to pick the most mundane way to die possible. Sometimes I think I want to go out in my sleep, with no pomp or circumstances whatsoever.

It might be best to do that, and avoid all the messier ways, like sword fights with giants and skydiving snafus. That way, everyone will have a semblance of closure. Instead of, "If only he would have spent more time in the gym practicing his melee skills (because everyone knows giants have a resistance to elemental spells)," it would be more like:

"How did he die?"

"Why, in his sleep."

"Oh. Well that's not very dramatic."

"Why no, not at all."

So which is it? After surviving cancer, I kind of get the notion that I won't be able to pick. The natural progression (or random assertion of unconscious power) of the Universal DJ really doesn't leave any room for requests. As much as I go back and forth between two extremes, I doubt that anything that has any control over how I go out cares in the least. It's going to happen the way it does. It almost did already, in a completely senseless and eye-opening kind of way.

Whatever it is, I hope that the way I choose to live inspires someone. Anyone. And that the manner in which I leave this place is entirely washed away in the memory of what I added to it.

Image credits: Top -- Monster Shower Sign, by derekdavalos via deviantart; Middle -- Horse Sleep, by Ian Webb via flickr; Mid Bottom -- Studying and Sleeping, by mrehan via flickr; Bottom -- Death Rides a Pale Trike, by Marcus Ranum via deviantart

Other people are also aware of this fact. I was crossing the street the other day with my friend Darrell, and when we got into the bus lane he held out his hand and said, "Watch out for buses. You don't want to be run over by a bus after you lived through cancer." And I'd say that's pretty accurate.

On the other hand, after surviving a horrible, traumatizing disease, it's easy to want to pick the most mundane way to die possible. Sometimes I think I want to go out in my sleep, with no pomp or circumstances whatsoever.

|

| "You planning to get up soon? Nope? Okay then." |

It might be best to do that, and avoid all the messier ways, like sword fights with giants and skydiving snafus. That way, everyone will have a semblance of closure. Instead of, "If only he would have spent more time in the gym practicing his melee skills (because everyone knows giants have a resistance to elemental spells)," it would be more like:

"How did he die?"

"Why, in his sleep."

"Oh. Well that's not very dramatic."

"Why no, not at all."

|

| Something like this might be pretty ideal: *Read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, DEAD* |

So which is it? After surviving cancer, I kind of get the notion that I won't be able to pick. The natural progression (or random assertion of unconscious power) of the Universal DJ really doesn't leave any room for requests. As much as I go back and forth between two extremes, I doubt that anything that has any control over how I go out cares in the least. It's going to happen the way it does. It almost did already, in a completely senseless and eye-opening kind of way.

|

| "I'm coming for ya. You know, eventually." |

Whatever it is, I hope that the way I choose to live inspires someone. Anyone. And that the manner in which I leave this place is entirely washed away in the memory of what I added to it.

Image credits: Top -- Monster Shower Sign, by derekdavalos via deviantart; Middle -- Horse Sleep, by Ian Webb via flickr; Mid Bottom -- Studying and Sleeping, by mrehan via flickr; Bottom -- Death Rides a Pale Trike, by Marcus Ranum via deviantart

Labels:

Cancer,

Death and Dying,

Facing Fear,

Self-Awareness

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

I Used To Smile All The Time

| Yesterday, I punched out a smiley face in the big pile of soap in the sink. Because everything deserves to be happy. |

Recently, my girlfriend told me to smile more. I was upset about this, because I tend to think I'm one of the happiest and most carefree people in the world. I have the history of manifesting positivity in the face of great tragedy to prove it. After I thought about it, however, I began to realize that although I think about the world now in very clear, concise modes, and although having such a clarity of perspective is inexplicably amazing, it doesn't necessarily mean that happiness will automatically follow.

I've been under a dark cloud for a long time, and my goals and my perception have been crystal clear since I was diagnosed. "I want this, this, and this," I said, as soon as I found out I had cancer. And I immediately set out to achieve those things. Some of them were easy, others of them aren't yet fully realized. I'm still hurting in certain ways after my experience, and the fact that I'm focusing on ways to fix that, instead of complaining and feeling sorry for myself is great, but it doesn't mean that it makes me happy, entirely. Because happy is an attitude, and I'm working on that. I still feel like I'm happier than the average bear, especially considering I know for a fact it's worthless to go through life being anything but. I just think I've been too concerned lately about conditional happiness. "When I get XYZ, I can finally relax..." Except that getting to XYZ is a huge journey, full of unforeseen obstacles and circumstances. And you still have to live your life while you get there. This is a pretty common attitude, and it manifests itself in several ways:

"When I get that promotion I can finally relax" -- Spoiler alert; it'll never be enough money.

"When I meet someone who makes me happy, everything will get better," -- Not necessarily; you generally need to be happy with yourself in order to attract someone in the first place.

"When I lose the extra weight, I'll be so much happier," -- I don't know, will you? You'll still be you. Be happy now, and lose the weight if you want to, not because you feel pressured to do so.

Conditions, conditions, conditions. It doesn't matter what level of priority they have in the grand scheme of things, all the way from "I'm unhappy at my job and won't be satisfied until I get a new one," and all the way to, "I'm killing my family financially post-cancer and need a book deal soon or we'll all starve." Conditions are a matter of perspective, but that's a thought for another time.

So, stop focusing on the conditional. It'll be great when it comes. But deal with your life while you have it, in the most fundamentally satisfying way possible. Because, seriously, what's the alternative?

Friday, August 9, 2013

I Wrote My Will at 26: Part 3, Health and Finance

I felt

selfish for writing my letter, and sending it out to close friends I knew would

follow through on my wishes. I only

asked that my family be looked after when I was gone. Most of the guilt came from the fact that I

hadn't really been able to look after them myself yet. My family had always looked after me, and

supported me monetarily when the occasion called for it. After my first year in NYC, I began to gain

financial independence. I worked in

project management and brought home a decent salary. But I was a contracted employee, and

eventually my contract ended. It wasn't

long before I was on my own again, with a dwindling savings account in a city

that's prohibitively expensive. I spent

a few months toying with the idea of writing for a living, and I even worked on

a book project. The money was going

fast, and I was only able to work a few days on another project. It was at that point I noticed that something

was wrong, and a cancer diagnosis promptly followed. I didn't have much of an opportunity to pick

myself back up after that. It was on to

surgery and immunotherapy instead. I

didn't fully know it yet, but my working days would be over for a while.

I

wondered if I'd actually done something wrong.

If I'd made a mistake and hadn't prepared to the best of my ability,

even though I could never have predicted what happened. All the same, I began to wonder what I should

have had in place at that point, in order to protect myself against unexpected

hardship. To answer that question, I

spoke with Bryan Mills, a financial consultant with Investors Capital.

|

| "I'm not made of money, but my clothes are" |

"One

of the biggest things I always ask someone I speak to is, do you have six

months of living expenses in the bank?

Six to twelve of months of real cash.

Whatever your monthly expenses are, you have to be able to cover at

least six months." It's no secret

that the average person needs to be saving, in order to cover their bases. But how do you go about this? "Write down what's called a

T-Chart," says Mills. "Income

on the right side, outflow on the left.

Write down every single expense: food, bills, car, gas, insurance,

travel. Go through line by line and see

if there are things you can cut if you need to."

Seems

simple enough. But what about when

something serious happens? What can the

average person do to protect themselves in case of an unexpected health

crisis? "Level premium term life

insurance is important for everyone to have," says Mills. "You can usually get it dirt cheap. The average cost of a funeral today is over

$10,000. A 20-30 year term policy is

relatively easy to qualify for and would cover the expense, instead of leaving

your family to pay out of pocket."

Age and health are a factor though, and policies will cost you more as

you get older. "Most people think

they're safe. 'My company is going to

give me all this insurance,' they think.

But what happens if you leave the company? Most group insurance isn't portable. Personal insurance is the best way to make

sure you're covered. And it has to be

through a company with a superior credit rating, otherwise they might not be

able to make good on their obligations in a really bad situation."

What if

you're just starting out in life? And

you can't afford a term policy, even though Bryan would argue that a lot of

them are very affordable, there are still instances in which any expenditure

seems like too much.

"Budget

yourself," says Mills. "Don't

spend wildly or erratically. You can

treat yourself, but really be conscious about what you're spending. There are apps that can help you."

Apps! Apps!

Of course! As a millennial, born

into an era of increasing technological dependence, I was very happy to hear

that. In my day-to-day adventuring, I

use a host of apps to make life easier, to entertain myself, and to annoy as

many people as possible. And so I

figured that being a financial consultant, Bryan would have the skinny on the

best gadgets in the financial field.

Turns out, he does. So what are

these magnificent software-laden golden geese?

Bryan gives us the rundown:

From the

glorious minds behind Mint.com, the app version of the site provides all of

your financial needs at the tips of your fingers (or thumbs). It tracks your spending habits and cash flow,

and creates a personalized budget based on your needs. Just add your banks and credit cards, and

watch your custom graphs load up and head deep into the red (oh, that doesn't

happen to everyone?).

Run by the Life and Health Insurance

Foundation for Education, a nonprofit that helps people find the insurance

that's right for them. They offer options based on your current needs,

providing various calculator and estimator tools to help you figure out what

kind of coverage you require. They have an Iphone app, and a website with

resources for consumers and advisers alike.

This is

Bryan's very own app. "For someone

who just started a job or is new to the workforce, it'll help you plan for the

future," he explains. His goal is

to get you from here to a healthy retirement, without pushing expensive

products down your throat. The app is

completely unbiased, and comes with two categories: "Retire Logix,"

for those looking to plan for the long-term, and "Student Logix,"

designed specifically for the academics among us. Anytime you feel like talking to Bryan in

more detail, click on "Consult with Bryan?" and you can dial him up or

send him an email. I personally send him

life-sized cardboard cutouts of my face, but he tells me that emails work just

as well. Retire Logix was rated among

the top 100 apps of 2011 by Money Magazine.

It turns

out there are options for protecting yourself financially in a crisis. Granted, it's very difficult to manage, and

no one knows this better than myself.

But I'm trying my best to get back on my feet, and if you're looking to

do so as well, I hope this information will be of use.

Image Credits: Top -- Pumice on 20 dollars, by Robert DuHamel via Wikimedia Commons; Middle -- I'm not made of money, but my clothes are, by Craighton Miller via flickr; Bottom -- I am PRETTY give me MONEY, by dtchn via deviantart

Disclosure:

I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not

receiving compensation for it. Bryan E.

Mills is a financial consultant who offers securities through Investors Capital

Corporation. Member FINRA/SIPC. 800-949-1422.

The views and opinions offered by Bryan Mills in this piece should not

be construed as specific investment advice.

You should consult an investment professional regarding your unique

situation.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

Jackie Chan Dies on the Internet Every Five Minutes

Yes, it's true folks. The interwebs doesn't lie. It's very sad; believe me, I know. But Jackie Chan, the action star whose movies I grew up watching, is dying at a rate of at least once every five minutes.

"How can we stop this from happening?" you might be asking yourself. Well -- and I legitimately believe this -- the only way to stop Jackie Chan from dying on the internet every five minutes is to buy my book, Astral Imperium And Other Stories. Otherwise, he may never recover. You might also decide to donate vast sums of money to a charity I invented just now as I'm typing this, called Save theWhales, Children, Homeless Ostrich Farmers, Jackie Chans By Donating Your Entire Net Worth To My Fake Charity (identified by the easy-to-remember acronym: STWCHOFJCBDYENWTMFC).

I hope at least someone is sitting down after a long day at work, reading this and thinking, "Yes, that seems legit. I will do these things to save Jackie."

My question is: Why do people want other people dead so very much? What's going on here?

We are, as a culture, fascinated with tragedy. Ironically fascinated. We push death on others just as quickly (if not more quickly) than we push it away from ourselves. We're just as likely to slow down along the highway to crane our necks at accidents, staring at crumpled cars pulled to the shoulder and spread open by the jaws of life, as we are to hope that something like that never happens to us.

Celebrities are easy targets -- they're highly visible and often idolized. What's more gripping than a story about the fall of an idol? Tragedy gets ratings. But the problem with the pursuit of ratings is the culture of yellow journalism it creates. Why rush Jackie into the grave? I'm sure he's a little more than weirded out about it. In my opinion, it would be much easier not to make designs on him; he's going to go at some point anyway. We all are. You can write about it then. Why not enjoy the time we have, instead of obsessing over when it's going to end?

.jpg) |

| Image: Gage Skidmore from Peoria, AZ, United States of America (Jackie Chan Uploaded by maybeMaybeMaybe) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

"How can we stop this from happening?" you might be asking yourself. Well -- and I legitimately believe this -- the only way to stop Jackie Chan from dying on the internet every five minutes is to buy my book, Astral Imperium And Other Stories. Otherwise, he may never recover. You might also decide to donate vast sums of money to a charity I invented just now as I'm typing this, called Save the

I hope at least someone is sitting down after a long day at work, reading this and thinking, "Yes, that seems legit. I will do these things to save Jackie."

My question is: Why do people want other people dead so very much? What's going on here?

We are, as a culture, fascinated with tragedy. Ironically fascinated. We push death on others just as quickly (if not more quickly) than we push it away from ourselves. We're just as likely to slow down along the highway to crane our necks at accidents, staring at crumpled cars pulled to the shoulder and spread open by the jaws of life, as we are to hope that something like that never happens to us.

Celebrities are easy targets -- they're highly visible and often idolized. What's more gripping than a story about the fall of an idol? Tragedy gets ratings. But the problem with the pursuit of ratings is the culture of yellow journalism it creates. Why rush Jackie into the grave? I'm sure he's a little more than weirded out about it. In my opinion, it would be much easier not to make designs on him; he's going to go at some point anyway. We all are. You can write about it then. Why not enjoy the time we have, instead of obsessing over when it's going to end?

Labels:

Celebrity Death Hoax,

Jackie Chan,

Yellow Journalism

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

I Wrote My Will at 26: Part 2, Health Troubles and the Law

If you're thinking of putting your own last wishes into writing, or even leaving a crummy bag of sand behind for your loved ones to sift through, there are a few things you should know. First off, I didn't have a legal bone in my body back then, and at this point the makeup of my bones is still pretty ambiguous, so please don't take this as a substitute for legal advice; it's a series of guidelines I've come by through my own experience with end-of-life matters. If you have legitimate concerns, be sure to talk to an attorney.

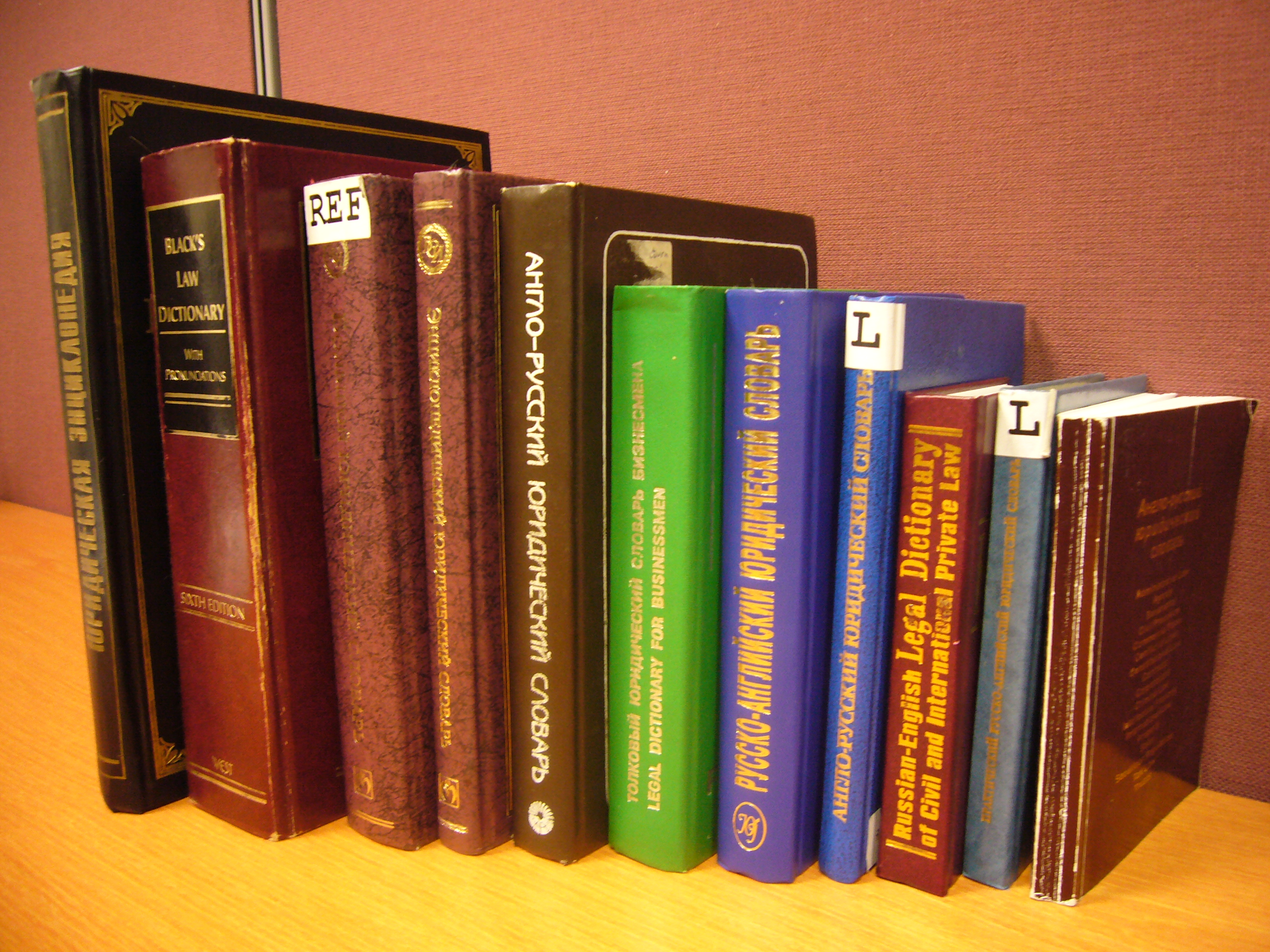

|

| Or maybe become an attorney yourself. You can start by reading all of these highly entertaining tomes. Credit: Leonid Dzhepko, Legal Translator |

And if you don't have time to go to law school, you can try some practical solutions instead. Turns out there are things that everyone can, and should, do, without shelling out extravagant legal fees and bankrupting themselves even further in the midst of a crisis. It's important to be aware of your options, so that if you need to, you can get your affairs in order quickly and efficiently. Recently, I sat down with Peter Ollen, attorney and owner at OllenLegal.com, and he told me just how to do that.

"The most important thing," he says, is to "have a properly executed will, witnessed and notarized. And make sure it's retrievable." This is the ideal scenario. It seems simple, but an an ABC poll from last August suggests that only half of all people have a will. A 2011 article from Business Insider puts the number of people without a will closer to 60%. And the percentage of young adults under thirty who haven't penned their last wishes is reported to be 92%. Very basically, you need to have everything you want or need written out in detail, make sure it's legally binding, and know where to find it. "If not," Ollen says, "There's a default pecking order. Absent of a will, spouse or parents make your decisions." There are also taxes involved with death, and you have to make sure all those pesky bills are paid, otherwise loved ones may get stuck with them.

But what if you're young, like say, my age, and something happens to you, similar to what I went through? How do you have your affairs together then, when you've barely started out in life? "There are resources online," says Ollen. "You can buy forms from LegalZoom.com, for instance, that are guaranteed resources. You can also reach out to your state bar association; they have pro bono and basic guidance available for these situations. If you don't have the resources to get an attorney, reach out to LegalZoom or other document depos. They can offer guidance and the state bar may be able to fill out the forms for you. And, if you're worried about your time or escalating situation, give someone power of attorney so they can handle all this for you, while you focus on the bigger issues."

|

| These guys know what's up. Credit: Daniel Schwen |

You can't always think clearly in the midst of a health crisis. I know I couldn't. So it's a good idea to get things squared away before you ever get into one. If you're getting to the point where it's difficult to juggle, Ollen suggests that you assign someone power of attorney. Make sure it's someone you trust, like a family member or spouse. They'll handle all the legal decisions for you, while you focus on what's really important -- your health.

I didn't have a will going into my cancer diagnosis, or a power of attorney. I ended up writing a letter that I would have tried to pass off as a will had things gone awry. But simply having something in writing isn't enough. Unless, like me, the point of leaving something behind was more for the message you planned to send your family and friends, than it was for the material goods and wealth. Even so, what little you have to give could inspire debate among your loved ones, and even turmoil. Any amount of stressing over who gets what in a time of loss can trigger intense emotional reactions. It's better to be safe and settled, than not have a plan at all.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

I Wrote My Will at 26

|

| "And my collection of geographically accurate boogers goes to..." |

I wrote my will at the age of 26. It's infused with comedic zingers, and is in no way legal -- but hey, it's a will, nonetheless.

During the period leading up to my second surgery, after I was diagnosed with cancer at 25, I wrote what would become a symbolic offering of what little I had in those days. I wanted to have something in writing that would tie up all the loose ends in my young life. Turns out, having lived only a quarter of a century, there weren't very many loose ends to worry about. Though I'd heard that it's better to have something in writing than to check out without making any kind of arrangements. Turns out that isn't entirely accurate, but I didn't know that at the time. So I drafted this letter. No one knows that I did this, not even my family.

At the time, I was doing a lot of sitting around and feeling sorry for myself. I laid on the couch at my parents' townhouse, watching TV, curled up under a snuggie, slowly losing the ability to cope with my evolving circumstances. Mostly though, I was feeling sorry that I had to leave my family, and that I had nothing to offer that would soften the blow. The thought of dying so early, loved ones gathered around to bury me, their faces twisted in mourning, was too much to bear. It spawned thoughts of my parents splitting up, my sister's new marriage falling apart, and all three of them slipping further into the depths of grief, never to return. And all that would be my fault. I would be the cause of so much suffering for the people I cared about most.